Columbia Records, is an American record label owned by Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese conglomerate Sony. It was founded in 1887, evolving from the American Graphophone Company, the successor to the Volta Graphophone Company. Columbia is the oldest surviving brand name in the recorded sound business, and the second major company to produce records. From 1961 to 1990, Columbia recordings were released outside North America under the name CBS Records to avoid confusion with EMI’s Columbia Graphophone Company.

Columbia is one of Sony Music’s four flagship record labels, alongside former longtime rival RCA Records, as well as Arista Records and Epic Records.

Columbia is one of Sony Music’s four flagship record labels, alongside former longtime rival RCA Records, as well as Arista Records and Epic Records.

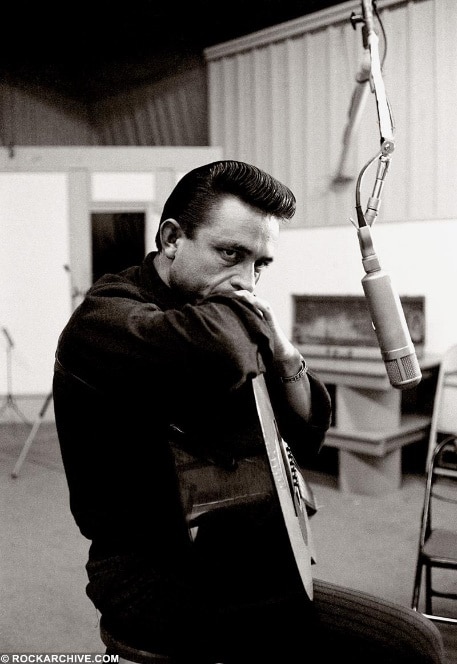

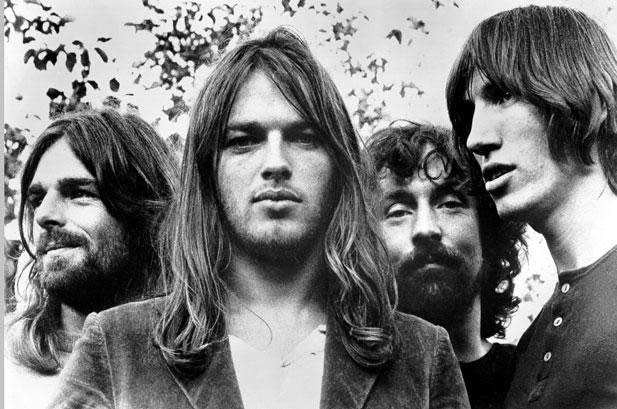

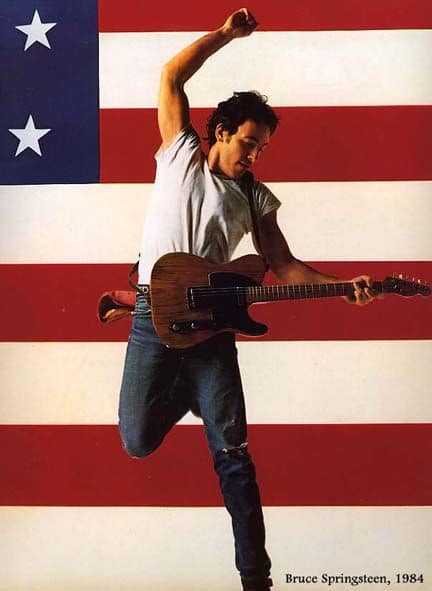

Artists who have recorded for Columbia include AC/DC, Aerosmith, Louis Armstrong, Tony Bennett, Blind Willie Johnson, Blue Öyster Cult, Dave Brubeck, The Byrds, Johnny Cash, The Clash, Miles Davis, Rosemary Clooney, Neil Diamond, Bob Dylan, Earth, Wind & Fire, Duke Ellington, Erroll Garner, Benny Goodman, Adelaide Hall, Billy Joel, Janis Joplin, John Mayer, George Michael, Billy Murray, New York Philharmonic, Pink Floyd, The Rolling Stones, Santana, Frank Sinatra, Simon and Garfunkel, Bessie Smith, Bruce Springsteen, Barbra Streisand, System of a Down, Bonnie Tyler, Paul Whiteman, Andy Williams, Pharrell Williams, Paul McCartney and Wings, Bill Withers, and Joe Zawinul.

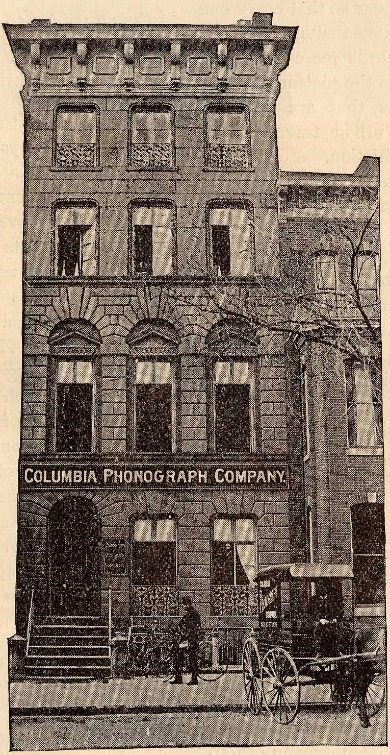

The Columbia Phonograph Company was founded in 1887 by stenographer, lawyer and New Jersey native Edward D. Easton (1856–1915) and a group of investors. It derived its name from the District of Columbia, where it was headquartered. At first it had a local monopoly on sales and service of Edison phonographs and phonograph cylinders in Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Delaware. As was the custom of some of the regional phonograph companies, Columbia produced many commercial cylinder recordings of its own, and its catalogue of musical records in 1891 was 10 pages.

Columbia’s ties to Edison and the North American Phonograph Company were severed in 1894 with the North American Phonograph Company’s breakup.

Thereafter it sold only records and phonographs of its own manufacture. In 1902, Columbia introduced the “XP” record, a molded brown wax record, to use up old stock. Columbia introduced black wax records in 1903.

According to one source, they continued to mold brown waxes until 1904 with the highest number being 32601, “Heinie”, which is a duet by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan. The molded brown waxes may have been sold to Sears for distribution (possibly under Sears’ Oxford trademark for Columbia products).

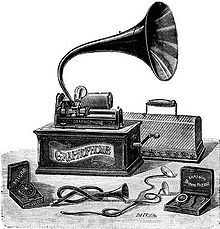

Columbia began selling disc records (invented and patented by Victor Talking Machine Company’s Emile Berliner) and phonographs in addition to the cylinder system in 1901, preceded only by their “Toy Graphophone” of 1899, which used small, vertically cut records. For a decade, Columbia competed with both the Edison Phonograph Company cylinders and the Victor Talking Machine Company disc records as one of the top three names in American recorded sound.

Columbia began selling disc records (invented and patented by Victor Talking Machine Company’s Emile Berliner) and phonographs in addition to the cylinder system in 1901, preceded only by their “Toy Graphophone” of 1899, which used small, vertically cut records. For a decade, Columbia competed with both the Edison Phonograph Company cylinders and the Victor Talking Machine Company disc records as one of the top three names in American recorded sound.

In order to add prestige to its early catalog of artists, Columbia contracted a number of New York Metropolitan Opera stars to make recordings . These stars included Marcella Sembrich, Lillian Nordica, Antonio Scotti and Edouard de Reszke, but the technical standard of their recordings was not considered to be as high as the results achieved with classical singers during the pre–World War I period by Victor, Edison, England’s His Master’s Voice (The Gramophone Company Ltd.) or Italy’s Fonotipia Records. After an abortive attempt in 1904 to manufacture discs with the recording grooves stamped into both sides of each disc not just one in 1908 Columbia commenced successful mass production of what they called their “Double-Faced” discs, the 10-inch variety initially selling for 65 cents apiece. The firm also introduced the internal-horn “Grafonola” to compete with the extremely popular “Victrola” sold by the rival Victor Talking Machine Company.

During this era, Columbia used the “Magic Notes” logo a pair of sixteenth notes (semiquavers) in a circle both in the United States.

Columbia stopped recording and manufacturing wax cylinder records in 1908, after arranging to issue celluloid cylinder records made by the Indestructible Record Company of Albany, New York, as “Columbia Indestructible Records”. In July 1912, Columbia decided to concentrate exclusively on disc records and stopped manufacturing cylinder phonographs, although they continued selling Indestructible’s cylinders under the Columbia name for a year or two more.

Columbia was split into two companies, one to make records and one to make players. Columbia Phonograph was moved to Connecticut, and Ed Easton went with it. Eventually it was renamed the Dictaphone Corporation.

In late 1922, Columbia went into receivership. The company was bought by its English subsidiary, the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1925 and the label, record numbering system, and recording process changed. On February 25, 1925, Columbia began recording with the electric recording process licensed from Western Electric. “Viva-tonal” records set a benchmark in tone and clarity unequaled on commercial discs during the 78-rpm era. The first electrical recordings were made by Art Gillham, the “Whispering Pianist”. In a secret agreement with Victor, electrical technology was kept secret to avoid hurting sales of acoustic records.

In late 1922, Columbia went into receivership. The company was bought by its English subsidiary, the Columbia Graphophone Company in 1925 and the label, record numbering system, and recording process changed. On February 25, 1925, Columbia began recording with the electric recording process licensed from Western Electric. “Viva-tonal” records set a benchmark in tone and clarity unequaled on commercial discs during the 78-rpm era. The first electrical recordings were made by Art Gillham, the “Whispering Pianist”. In a secret agreement with Victor, electrical technology was kept secret to avoid hurting sales of acoustic records.

In 1926, Columbia acquired Okeh Records and its growing stable of jazz and blues artists, including Louis Armstrong and Clarence Williams. Columbia had already built a catalog of blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith in their 14000-D Race series. Columbia also had a successful “Hillbilly” series (15000-D). In 1928, Paul Whiteman, the nation’s most popular orchestra leader, left Victor to record for Columbia. During the same year, Columbia executive Frank Buckley Walker pioneered some of the first country music or “hillbilly” genre recordings with the Johnson City sessions in Tennessee, including artists such as Clarence Horton Greene and “Fiddlin'” Charlie Bowman. He followed that with a return to Tennessee the next year, as well as recording sessions in other cities of the South.

In 1929 Ben Selvin became house bandleader and A. & R. director. Other favorites in the Viva-tonal era included Ruth Etting, Paul Whiteman, Fletcher Henderson, Ipana Troubadours (a Sam Lanin group), and Ted Lewis. Columbia used acoustic recording for “budget label” pop product well into 1929 on the labels Harmony, Velvet Tone (both general purpose labels), and Diva (sold exclusively at W.T. Grant stores). When Edison Records folded, Columbia was the oldest surviving record label.

Columbia ownership separation (1931–1936)

In 1931, the British Columbia Graphophone Company (itself originally a subsidiary of American Columbia Records, then to become independent, actually went on to purchase its former parent, American Columbia, in late 1929) merged with the Gramophone Company to form Electric & Musical Industries Ltd. (EMI). EMI was forced to sell its American Columbia operations (because of anti-trust concerns) and the Grigsby-Grunow Company, makers of the Majestic Radio were the purchaser. But Majestic soon fell on hard times. An abortive attempt in 1932 (around the same time that Victor was experimenting with its 331⁄3 “program transcriptions”) was the “Longer Playing Record”, a finer-grooved 10″ 78 with 4:30 to 5:00 playing time per side. Columbia issued about eight of, as well as a short-lived series of double-grooved “Longer Playing Record”s on its Clarion Records, Harmony and Velvet Tone labels. All these experiments were discontinued by mid-1932.

A longer-lived marketing ploy was the Columbia “Royal Blue Record,” a brilliant blue laminated product with matching label. Royal Blue issues, made from late 1932 through 1935, are particularly popular with collectors for their rarity and musical interest. The Columbia plant in Oakland, California, did Columbia’s pressings for sale west of the Rockies and continued using the Royal Blue material for these until about mid-1936.

With the Great Depression’s tightened economic stranglehold on the country, in a day when the phonograph itself had become a luxury, nothing slowed Columbia’s decline. It was still producing some of the most remarkable records of the day, especially on sessions produced by John Hammond and financed by EMI for overseas release. Grigsby-Grunow went under in 1934 and was forced to sell Columbia for a mere $70,000 to the American Record Corporation (ARC). This combine already included Brunswick as its premium label so Columbia was relegated to slower sellers such as the Hawaiian music of Andy Iona, the Irving Mills stable of artists and songs, and the still unknown Benny Goodman. By late 1936, pop releases were discontinued, leaving the label essentially defunct.

In 1935, Herbert M. Greenspon, an 18-year-old shipping clerk, led a committee to organize the first trade union shop at the main manufacturing factory in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Elected as president of the Congress of Industrial Unions (CIO) local, Greenspon negotiated the first contract between factory workers and Columbia management. In a career with Columbia that lasted 30 years, Greenspon retired after achieving the position of executive vice president of the company. The Columbia Records factory in Bridgeport (which closed in 1964) was converted into an apartment building called Columbia Towers.

As southern gospel developed, Columbia had astutely sought to record the artists associated with the emerging genre; for example, Columbia was the only company to record Charles Davis Tillman. Most fortuitously for Columbia in its Depression Era financial woes, in 1936 the company entered into an exclusive recording contract with the Chuck Wagon Gang, a hugely successful relationship which continued into the 1970s. A signature group of southern gospel, the Chuck Wagon Gang became Columbia’s bestsellers with at least 37 million records, many of them through the aegis of the Mull Singing Convention of the Air sponsored on radio (and later television) by southern gospel broadcaster J. Bazzel Mull (1914–2006).

Another event in this period that would prove to be of importance to Columbia was the 1937 hiring of talent scout, music writer, producer, and impresario John Hammond. Alongside his significance as a discoverer, promoter, and producer of jazz, blues, and folk artists during the swing music era, Hammond had already been of great help to Columbia in 1932–33. Through his involvement in the UK music paper Melody Maker, Hammond had arranged for the struggling US Columbia label to provide recordings for the UK Columbia label, mostly using the specially created Columbia W-265000 matrix series. Hammond recorded Fletcher Henderson, Benny Carter, Joe Venuti, Roger Wolfe Kahn and other jazz performers during a time when the economy was bad enough that many of them would not have had the opportunity to enter a studio and play real jazz. Hammond’s work for Columbia was interrupted by his service during World War II, and he had less involvement with the music scene during the bebop era, but when he returned to work as a talent scout for Columbia in the 1950s, his career proved to be of incalculable historical and cultural importance – the list of superstar artists he would discover and sign to Columbia over the course of his career included Charlie Christian, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Aretha Franklin, Bruce Springsteen and Stevie Ray Vaughan, and in the early 1960s Hammond would also exert an enormous cultural effect on the emerging rock music scene thanks to his championing of reissue LPs of the music of blues artists Robert Johnson and Bessie Smith.

CBS takes over (1938–1947)

In 1938 ARC, including the Columbia label in the US, was bought by William S. Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System for US$750,000. CBS revived the Columbia label in place of Brunswick and the Okeh label in place of Vocalion. CBS renamed the company Columbia Recording Corporation and retained control of all of ARC’s past masters, but in a complicated move, the pre-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters, as well as trademarks of Brunswick and Vocalion, reverted to Warner Bros. and Warners sold it all to Decca Records in 1941.

In 1938 ARC, including the Columbia label in the US, was bought by William S. Paley of the Columbia Broadcasting System for US$750,000. CBS revived the Columbia label in place of Brunswick and the Okeh label in place of Vocalion. CBS renamed the company Columbia Recording Corporation and retained control of all of ARC’s past masters, but in a complicated move, the pre-1931 Brunswick and Vocalion masters, as well as trademarks of Brunswick and Vocalion, reverted to Warner Bros. and Warners sold it all to Decca Records in 1941.

The Columbia trademark from this point until the late 1950s was two overlapping circles with the Magic Notes in the left circle and a CBS microphone in the right circle. The Royal Blue labels now disappeared in favor of a deep red, which caused RCA Victor to claim infringement on its Red Seal trademark (RCA lost the case).

The Columbia trademark from this point until the late 1950s was two overlapping circles with the Magic Notes in the left circle and a CBS microphone in the right circle. The Royal Blue labels now disappeared in favor of a deep red, which caused RCA Victor to claim infringement on its Red Seal trademark (RCA lost the case).

The blue Columbia label was kept for its classical music Columbia Masterworks Records line until it was later changed to a green label before switching to a gray label in the late 1950s, and then to the bronze that is familiar to owners of its classical and Broadway albums. Columbia Phonograph Company of Canada did not survive the Great Depression, so CBS made a distribution deal with Sparton Records in 1939 to release Columbia records in Canada under the Columbia name.

During the 1940s Columbia had a contract with Frank Sinatra. Sinatra helped boost Columbia in revenue. Sinatra recorded over 200 songs with Columbia which include his most popular songs from his early years. Other popular artists on Columbia included Benny Goodman (signed from RCA Victor), Count Basie, Jimmie Lunceford (both signed from Decca), Eddy Duchin, Ray Noble (both moved to Columbia from Brunswick), Kate Smith, Mildred Bailey, and Will Bradley.

In 1947, the company was renamed Columbia Records Inc. and founded its Mexican record company, Discos Columbia de Mexico.1948 saw the first classical LP Nathan Milstein’s recording of the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto. Columbia’s 33 rpm format quickly spelled the death of the classical 78 rpm record and for the first time in nearly fifty years, gave Columbia a commanding lead over RCA Victor Red Seal.

The LP record (1948–1959)

Columbia’s president Edward Wallerstein was instrumental in steering Paley towards the ARC purchase. He set his talents to his goal of hearing an entire movement of a symphony on one side of an album. Ward Botsford writing for the Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Issue of High Fidelity Magazine relates, “He was no inventor—he was simply a man who seized an idea whose time was ripe and begged, ordered, and cajoled a thousand men into bringing into being the now accepted medium of the record business.” Despite Wallerstein’s stormy tenure, in June 1948, Columbia introduced the Long Playing “microgroove” LP record format (sometimes written “Lp” in early advertisements), which rotated at 33⅓ revolutions per minute, to be the standard for the gramophone record for half a century. CBS research director Dr. Peter Goldmark played a managerial role in the collaborative effort, but Wallerstein credits engineer William Savory with the technical prowess that brought the long-playing disc to the public.

By the early 1940s, Columbia had been experimenting with higher fidelity recordings, as well as longer masters, which paved the way for the successful release of the LPs in 1948. One such record that helped set a new standard for music listeners was the 10″ LP reissue of The Voice of Frank Sinatra, originally released on March 4, 1946 as an album of four 78 rpm records, which was the first pop album issued in the new LP format. Sinatra was arguably Columbia’s hottest commodity and his artistic vision combined with the direction Columbia were taking the medium of music, both popular and classic, were well suited. The Voice of Frank Sinatra was also considered to be the first genuine concept album. Since the term “LP” has come to refer to the 12-inch 33 1⁄3 rpm vinyl disk, the first LP is the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor played by Nathan Milstein with Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic (then called the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York), Columbia ML 4001, found in the Columbia Record Catalog for 1949, published in July 1948. The other “LP’s” listed in the catalog were in the 10 inch format starting with ML 2001 for the light classics, CL 6001 for popular songs and JL 8001 for children’s records. The Library of Congress (Washington DC) now holds the Columbia Records Paperwork Archive which shows the Label order for ML 4001 being written on March 1, 1948. One can infer that Columbia was pressing the first LPs for distribution to their dealers for at least 3 months prior to the introduction of the LP in June 1948.The catalog numbering system has had minor changes ever since.

Columbia’s LPs were particularly well-suited to classical music’s longer pieces, so some of the early albums featured such artists as Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The success of these recordings eventually persuaded Capitol Records to begin releasing LPs in 1949. Even before the LP record was officially demonstrated, Columbia offered to share the new speed with rival RCA Victor, who initially rejected it and soon introduced their new competitive 45 RPM record. When it became clear that the LP was the preferred format for classical recordings, RCA Victor announced that the company would begin releasing its own LPs in January, 1950. This was quickly followed by the other major American labels. Decca Records in the U.K. was the first to release LPs in Europe, beginning in 1949. EMI would not fully adopt the LP format until 1955.

An “original cast recording” of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s South Pacific with Ezio Pinza and Mary Martin was recorded in 1949. Both conventional metal masters and tape were used in the sessions in New York City. For some reason, the taped version was not used until Sony released it as part of a set of CDs devoted to Columbia’s Broadway albums. Over the years, Columbia joined Decca and RCA Victor in specializing in albums devoted to Broadway musicals with members of the original casts. In the 1950s, Columbia also began releasing LPs drawn from the soundtracks of popular films.

Many album covers put together by Columbia and the other major labels were put together using one piece of cardboard (folded in half) and two paper “slicks,” one for the front and one for the back. The front slick bent around the top, bottom, and left sides (the right side is open for the record to be inserted into the cover) and glued the two halves of cardboard together at the top and bottom. The back slick is pasted over the edges of the pasted-on front slick to make it appear that the album cover is one continuous piece.

Columbia discovered that printing two front cover slicks, one for mono and one for stereo, was inefficient and therefore needlessly costly. Starting in the summer of 1959 with some of the albums released in August, they went to the “paste-over” front slick, which had the stereo information printed on the top and the mono information printed on the bottom. For stereo issues, they moved the front slick down so the stereo information was showing at the top, and the mono information was bent around the bottom to the back and “pasted over” by the back slick. Conversely, for a mono album, they moved the slick up so the mono information showed at the bottom, and the stereo information was pasted over.

The 1950s

In 1951, Columbia US began issuing records in the 45 rpm format RCA Victor had introduced two years earlier. The same year, Ted Wallerstein retired as Columbia Records chairman; and Columbia US also severed its decades-long distribution arrangement with EMI and signed a distribution deal with Philips Records to market Columbia recordings outside North America. EMI continued to distribute Okeh and later Epic label recordings until 1968. EMI also continued to distribute Columbia recordings in Australia and New Zealand. American Columbia was not happy with EMI’s reluctance to introduce long playing records.

Columbia became the most successful non-rock record company in the 1950s after it lured producer and bandleader Mitch Miller away from the Mercury label in 1950. Despite its many successes, Columbia remained largely uninvolved in the teenage rock’n’roll market until the mid-1960s, despite a handful of crossover hits, largely because of Miller’s famous (and frequently expressed) loathing of rock’n’roll. (Miller was a classically trained oboist who had been a friend of Columbia executive Goddard Lieberson since their days at the Eastman School of Music in the 1930s.) Miller quickly signed up Mercury’s biggest artist at the time, Frankie Laine, and discovered several of the decade’s biggest recording stars including Tony Bennett, Mahalia Jackson, Jimmy Boyd, Guy Mitchell (whose stage surname was taken from Miller’s first name), Johnnie Ray, The Four Lads, Rosemary Clooney, Ray Conniff, Jerry Vale and Johnny Mathis. He also oversaw many of the early singles by the label’s top female recording star of the decade, Doris Day.

In 1953, Columbia formed a new subsidiary label Epic Records. 1954 saw Columbia end its distribution arrangement with Sparton Records and form Columbia Records of Canada. Despite the appearance of favoring a country music genre, Columbia bid $15,000 for Elvis Presley’s contract from Sun Records in 1955. Miller made no secret of the fact that he was not a fan of rock music and was saved from having to deal with it when Presley’s manager, Colonel Tom Parker, turned down their offer and signed Presley with RCA Victor. However, Columbia did sign two Sun artists in 1958: Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins.

With 1954, Columbia US decisively broke with its past when it introduced its new, modernist-style “Walking Eye” logo, designed by Columbia’s art director S. Neil Fujita. This logo actually depicts a stylus (the legs) on a record (the eye); however, the “eye” also subtly refers to CBS’s main business in television, and that division’s iconic Eye logo. Columbia continued to use the “notes and mike” logo on record labels and even used a promo label showing both logos until the “notes and mike” was phased out (along with the 78 in the US) in 1958. In Canada, Columbia 78s were pressed with the “Walking Eye” logo in 1958. The original Walking Eye was tall and solid; it was modified in 1961 to the familiar one still used today (pictured on this page), despite the fact that the Walking Eye was used only sporadically during most of the 1990s.

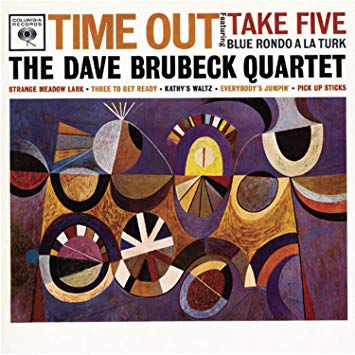

Although the onset of long-playing vinyl “hi-fi” records coincided with the public’s loss of interest in big bands, Columbia maintained Duke Ellington under contract, capturing the historic moment when Ellington’s band provoked a post-midnight frenzy (followed by international headlines) at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, which proved not only a boost to the venerable bandleader and the barely established venue of the outdoor music festival but a harbinger of the musical love-fest that was Woodstock. Under new head producer George Avakian, Columbia became the most vital label to the general public’s appreciation and understanding (with help from Avakian’s prolific and perceptive play-by-play liner notes) of America’s indigenous art, releasing the most important LP’s by the music’s founding father, Louis Armstrong, but also signing to long-term contracts Dave Brubeck and Miles Davis, the two modern jazz artists who would in 1959 record albums that remain—more than a half century later—among the best-selling jazz albums by any label viz., Time Out by the Brubeck Quartet and, to an even greater extent, Kind of Blue by the Davis Sextet, which, in 2003, appeared as number 12 in Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Albums Of All Time”.With another producer, Teo Macero, a skilled modernist composer himself, Columbia cemented contracts with jazz giants Thelonious Monk and Charles Mingus, while Macero became a key agent in recording and representing—through attention-grabbing, colorful—albums the protean faces of Miles Davis—from leading exponent of cool jazz and an explorer of the art of modal jazz through his sextet’s 1958 album Milestones to innovator and avatar of the marriage of jazz with rock and electronic sounds—commonly known as jazz fusion.

1954 was the eventful year of Columbia’s embracing small-group modern jazz—first, in the signing of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which resulted in the release of the on-location, best-selling jazz album (up to this time), Jazz Goes to College. Contemporaneously with Columbia’s first release of modern jazz by a small group, which was also the Brubeck Quartet’s debut on the label, was a Time Magazine cover story on the phenomenon of Brubeck’s success on college campuses. The humble Dave Brubeck demurred, saying that the second Time Magazine cover story on a jazz musician (the first featured Louis Armstrong’s picture) had been earned by Duke Ellington, not himself. Within two years Ellington’s picture would appear on the cover of Time Magazine, following his “wild” success at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. Ellington at Newport, recorded on Columbia, was also the bandleader-composer-pianist’s best-selling album. Moreover, this exclusive trinity of jazz giants featured on Time Magazine were all Columbia artists. (In the early 1960s Columbia jazz artist Thelonious Monk would be afforded the same honor.)

1954 was the eventful year of Columbia’s embracing small-group modern jazz—first, in the signing of the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which resulted in the release of the on-location, best-selling jazz album (up to this time), Jazz Goes to College. Contemporaneously with Columbia’s first release of modern jazz by a small group, which was also the Brubeck Quartet’s debut on the label, was a Time Magazine cover story on the phenomenon of Brubeck’s success on college campuses. The humble Dave Brubeck demurred, saying that the second Time Magazine cover story on a jazz musician (the first featured Louis Armstrong’s picture) had been earned by Duke Ellington, not himself. Within two years Ellington’s picture would appear on the cover of Time Magazine, following his “wild” success at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. Ellington at Newport, recorded on Columbia, was also the bandleader-composer-pianist’s best-selling album. Moreover, this exclusive trinity of jazz giants featured on Time Magazine were all Columbia artists. (In the early 1960s Columbia jazz artist Thelonious Monk would be afforded the same honor.)

Columbia changed distributors in Australia and New Zealand in 1956 when the Australian Record Company picked up distribution of U.S. Columbia product to replace the Capitol Records product which ARC lost when EMI bought Capitol. As EMI owned the Columbia trademark at that time, the U.S. Columbia material was issued in Australia and New Zealand on the CBS Coronet label.

In the same year, former Columbia A&R manager Goddard Lieberson was promoted to President of the entire CBS recording division, which included Columbia and Epic, as well as the company’s various international divisions and licensees. Under his leadership the corporation’s music division soon overtook RCA Victor as the top recording company in the world, boasting a star-studded roster of artists and an unmatched catalogue of popular, jazz, classical and stage and screen soundtrack titles. Lieberson, who had joined Columbia as an A&R manager in 1938, was noted for both his personal elegance and his dedication to quality, overseeing the release of many hugely successful albums and singles, as well as championing prestige releases that sold relatively poorly, and even some titles that had very limited appeal, such as complete editions of the works of Arnold Schoenberg and Anton von Webern. One of his first major successes was the original cast soundtrack of My Fair Lady, which sold over 5 million copies worldwide in 1957, becoming the most successful LP ever released up to that time. Lieberson also convinced long-serving CBS President William S. Paley to become the sole backer of the original Broadway production, a $500,000 investment which subsequently earned the company some $32 million in profits.

In October 1958, Columbia, in time for the Christmas season, put out a series of “Greatest Hits” packages by such artists as Johnny Mathis, Doris Day, Guy Mitchell, Johnnie Ray, Jo Stafford, Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Frankie Laine and the Four Lads; months later, it put out another Mathis compilation as well as that of Marty Robbins. Only Mathis’ compilations charted, since there were only 25 positions on Billboard’s album charts at the time. However, the compilations were so successful that they led to Columbia doing such packages on a widespread basis, usually when an artist’s career was in decline.

Stereo

Although Columbia began recording in stereo in 1956, stereo LPs did not begin to be manufactured until 1958. One of Columbia’s first stereo releases was an abridged and re-structured performance of Handel’s Messiah by the New York Philharmonic and the Westminster Choir conducted by Leonard Bernstein (recorded on December 31, 1956, on 1⁄2 inch tape, using an Ampex 300-3 machine). Bernstein combined the Nativity and Resurrection sections, and ended the performance with the death of Christ. As with RCA Victor, most of the early stereo recordings were of classical artists, including the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Bruno Walter, Dimitri Mitropoulos, and Leonard Bernstein, and the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy, who also recorded an abridged Messiah for Columbia. Some sessions were made with the Columbia Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble drawn from leading New York musicians, which had first made recordings with Sir Thomas Beecham in 1949 in Columbia’s famous New York City studios. George Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra recorded mostly for Epic. When Epic dropped classical music, the roster and catalogue was moved to Columbia Masterworks Records.

Columbia released its first pop stereo albums in the summer of 1958. All of the first dozen or so were stereo versions of albums already available in mono. It wasn’t until September 1958, that Columbia started simultaneous mono/stereo releases. Mono records sold to the general public were subsequently discontinued in 1968. To celebrate the 10th anniversary of the introduction of the LP, in 1958 Columbia initiated the “Adventures in Sound” series that showcased music from around the world.

As far as the catalog numbering system went, there was no correlation between mono and stereo versions for the first few years. Columbia started a new CS 8000 series for pop stereo releases and figuring the stereo releases as some sort of specialty niche records, didn’t bother to link the mono and stereo numbers for two years. Masterworks classical LPs had an MS 6000 series, while showtunes albums on Masterworks were OS 2000. Finally, in 1960, the pop stereo series jumped from 8300 to 8310 to match Lambert, Hendricks & Ross Sing Ellington, the Lambert, Hendricks & Ross album issued as CL-1510. From that point, the stereo numbers on pop albums were exactly 6800 higher than the mono; stereo classical albums were the mono number plus 600; and showtunes releases were the mono number MINUS 3600. Only the last two digits in the respective catalog series’ matched.

Pop stereo LPs got into the high 9000s by 1970, when CBS Records revamped and unified its catalog numbering system across all its labels. Masterworks classical albums were in the 7000s, while showtunes stayed in the low 2000s.

The 1960s

Outing of “deep groove”

By the latter half of 1961, Columbia started using pressing plants with newer equipment. The “deep groove” pressings were made on older pressing machines, where the groove was an artifact of the metal stamper being affixed to a round center “block” to assure the resulting record would be centered. Newer machines used parts with a slightly different geometry, that only left a small “ledge” where the deep groove used to be. This changeover did not happen all at once, as different plants replaced machines at different times, leaving the possibility that both deep groove and ledge varieties could be original pressings. The changeover took place starting in late 1961.

CBS Records

In 1961, CBS ended its arrangement with Philips Records and formed its own international organization, CBS Records, in 1962, which released Columbia recordings outside the US and Canada on the CBS label. The recordings could not be released under the Columbia Records name because EMI operated a separate record label by that name, Columbia Graphophone Company, outside North America. This was the result of legal maneuvers which led to the creation of EMI in the early 1930s.

In 1961, CBS ended its arrangement with Philips Records and formed its own international organization, CBS Records, in 1962, which released Columbia recordings outside the US and Canada on the CBS label. The recordings could not be released under the Columbia Records name because EMI operated a separate record label by that name, Columbia Graphophone Company, outside North America. This was the result of legal maneuvers which led to the creation of EMI in the early 1930s.

While this happened, starting in late 1961, both the mono and the stereo labels of domestic Columbia releases started carrying a small “CBS” at the top of the label. This was not something that changed at a certain date, but rather, pressing plants were told to use up the stock of old (pre-CBS) labels first, resulting in a mixture of labels for some given releases. Some are known with the CBS text on mono albums, and not on stereo of the same album, and vice versa; diggings brought up pressings with the CBS text on one side and not on the other. Many, but certainly not all, of the early numbers with the “ledge” variation (i.e., no deep groove), had the small “CBS.” This text would be used on the Columbia labels until June, 1962.

Columbia’s Mexican unit, Discos Columbia, was renamed Discos CBS.

With the formation of CBS Records International, CBS started establishing its own distribution in the early 1960s, beginning in Australia. In 1960 CBS took over its distributor in Australia and New Zealand, the Australian Record Company (founded in 1936) including Coronet Records, one of the leading Australian independent recording and distribution companies of the day. The CBS Coronet label was replaced by the CBS label with the ‘walking eye’ logo in 1963. ARC continued trading under that name until the late 1970s when it formally changed its business name to CBS Australia.

Mitch Miller on television

In 1961, Columbia’s music repertoire was given an enormous boost when Mitch Miller, its A&R manager and bandleader, became the host of the variety series Sing Along with Mitch on NBC. The show was based on Miller’s ‘folksy’ but appealing ‘chorus’ style performance of popular standards. During its four-season run, the series promoted Miller’s “Singalong” albums, which sold over 20 million units, and received a 34% audience share when it was cancelled in 1964.

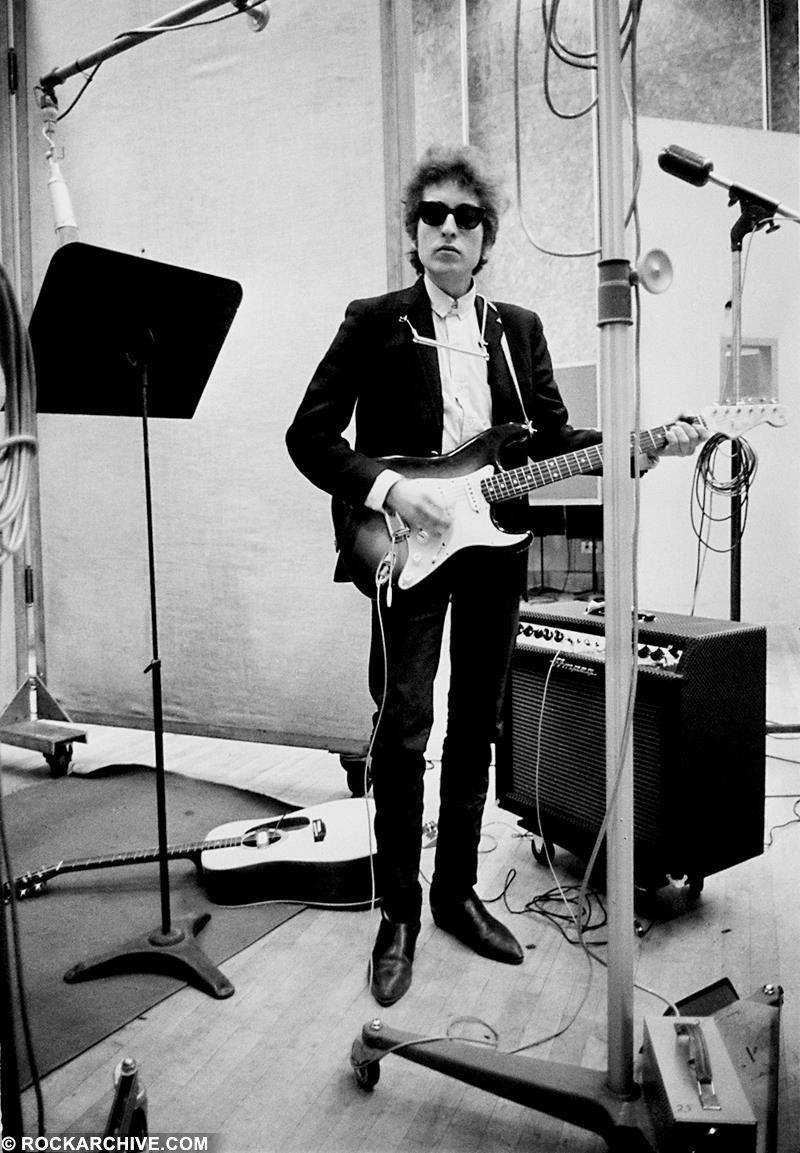

Bob Dylan

In September 1961, CBS A&R manager John Hammond was producing the first Columbia album by folk singer Carolyn Hester, who invited a friend to accompany her on one of the recording sessions. It was here that Hammond first met Bob Dylan, whom he signed to the label, initially as a harmonica player. Dylan’s self-titled debut album was released in March 1962 and sold only moderately. Some executives in Columbia dubbed Dylan “Hammond’s folly” and suggest that Dylan be dropped from the label. But John Hammond and Johnny Cash defended Dylan, who over the next four years became one of Columbia’s highest earning acts.

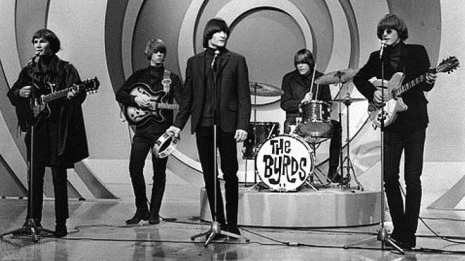

Over the course of the 1960s, Dylan achieved a prominent position in Columbia. His early folk songs were recorded by many acts and became hits for Peter, Paul & Mary and The Turtles. Some of these cover versions became the foundation of the folk rock genre. The Byrds achieved their pop breakthrough with a version of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man”. In 1965, Dylan’s controversial decision to ‘go electric’ and work with rock musicians divided his audience but catapulted him to greater commercial success with his 1965 hit single “Like a Rolling Stone”. Following his withdrawal from touring in 1966, Dylan recorded a large group of songs with his backing group The Band which reached other artists as ‘demo recordings’. These resulted in hits by Manfred Mann (“The Mighty Quinn”) and Brian Auger, Julie Driscoll & Trinity (“This Wheel’s On Fire”). Dylan’s late 1960s albums John Wesley Harding and Nashville Skyline became cornerstone recordings of the emergent country rock genre and influenced The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers.

Converting mono

Columbia’s engineering department developed a process for emulating stereo from a mono source. They called this process “Electronically Rechanneled for Stereo.” In the June 16, 1962, issue of Billboard magazine (page 5), Columbia announced it would issue “rechanneled” versions of greatest hits compilations that had been recorded in mono, including albums by Doris Day, Frankie Laine, Percy Faith, Mitch Miller, Marty Robbins, Dave Brubeck, Miles Davis, and Johnny Mathis.

Columbia’s rechanneling process involved a slight time delay and some bass-treble separation between channels. RCA Victor and Capitol (“Duophonic”) used similar processes, but the relatively large delay between channels resulted in a sound that has been described by collectors as “messy” (Duophonic) or “garbage can echo” (RCA Victor). Columbia’s rechanneling resulted in a sound similar to reverb, though some found it annoying.

Rock and roll

When the British Invasion arrived in January 1964, Columbia had no rock musicians on its roster except for Dion, who was signed in 1963 as the label’s first major rock star, and Paul Revere & the Raiders who were also signed in 1963. The label released a Merseybeat album, The Exciting New Liverpool Sound . Terry Melcher, son of Doris Day, produced the hard driving “Don’t Make My Baby Blue” for Frankie Laine, who had gone six years without a hit record. The song reached No. 51 on the pop chart and No. 17 on the easy listening chart.

Melcher and Bruce Johnston discovered and brought to Columbia The Rip Chords, a vocal group consisting of Ernie Bringas and Phil Stewart, and turned it into a rock group through production techniques. The group had hits in “Here I Stand”, a remake of the song by Wade Flemons, and “Hey Little Cobra”. Columbia saw the two recordings as a start to getting into rock and roll. Melcher and Johnston recorded several additional singles for Columbia in 1964 as “Bruce & Terry” and later as “The Rogues.” Melcher produced early albums by The Byrds and Paul Revere & the Raiders for Columbia while Johnston produced The Beach Boys for Capitol Records.

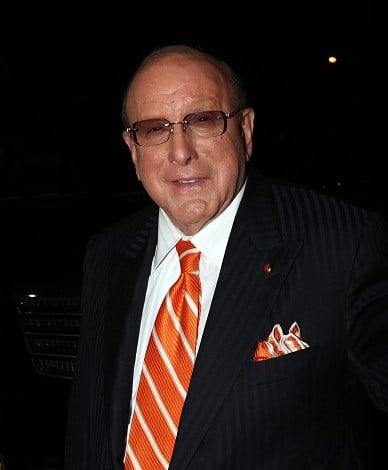

Ascension of Clive Davis

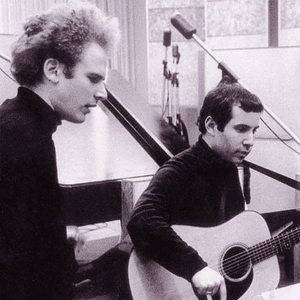

When Mitch Miller retired in 1965, Columbia was at a turning point. Miller’s disdain for rock and roll and pop rock had dominated Columbia’s A&R policy. The label’s only significant “pop” acts at the time were Bob Dylan, The Byrds, Paul Revere & The Raiders and Simon & Garfunkel. In its catalogue were other genres: classical, jazz and country, along with a select group of R&B artists, among them Aretha Franklin. Most historians noted that Columbia had problems marketing Franklin as a major talent in the R&B genre, which led to her leaving the label for Atlantic Records in 1967.

In 1967, Brooklyn-born lawyer Clive Davis became president of Columbia. Sales of Broadway soundtracks and Mitch Miller’s singalong series were waning. Pretax earnings had flattened to about $5 million annually. Following the appointment of Davis, the Columbia label became more of a rock music label, thanks mainly to Davis’s fortuitous decision to attend the Monterey International Pop Festival, where he spotted and signed several leading acts including Janis Joplin. Joplin led the way for several generations of female rock and rollers. However, Columbia/CBS still had a hand in traditional pop and jazz and one of its key acquisitions during this period was Barbra Streisand. She released her first solo album on Columbia in 1963 and remains with the label to this day. Additionally, the label kept Miles Davis on the roster, and his late 1960s recordings, In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew, pioneered a fusion of jazz and rock music.

A San Francisco group called Moby Grape had been gaining popularity on the West Coast, and were signed by Davis in 1967. As a way of introducing them to the world with a splash, they released their debut album, along with five singles from the album, all on the same day, June 6, 1967, 23 years following D-Day. The album hit made #24 on the Billboard 200, but the singles barely made a dent in the charts, the best performer being “Omaha,” which lasted a mere three weeks on the Hot 100 reaching only No. 88. The other charter, “Hey Grandma,” only reached the Bubbling Under chart and faded within a week. Also, there were some complaints about the obscene gesture made to the American flag on the front cover that had to be edited out on the second pressing, not to mention that the group started to decline in sales after that. The return on all the promotional budget for the singles realized nothing. Although the group made two more albums, this particular publicity stunt was never again attempted by Columbia or any other major label.

Simon & Garfunkel

Arguably the most commercially successful Columbia pop act of this period, other than Bob Dylan, was Simon & Garfunkel. The duo scored a surprise No. 1 hit in 1965 when CBS producer Tom Wilson, inspired by the folk-rock experiments of The Byrds and others, added drums and bass to the duo’s earlier recording of “The Sound of Silence” without their knowledge or approval. Indeed, the duo had already broken up some months earlier, discouraged by the poor sales of their debut LP, and Paul Simon had relocated to the UK, where he famously only found out about the single being a hit via the music press. The dramatic success of the song prompted Simon to return to the US; the duo reformed, and they soon became one of the flagship acts of the folk-rock boom of the mid-1960s. Their next album, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme, went to No. 4 on the Billboard album chart. The duo subsequently had a Top 20 single, “A Hazy Shade of Winter”, but progress slowed during 1966-67 as Simon struggled with writer’s block and the demands of constant touring. They shot back to the top in 1968 after Simon agreed to write songs for the Mike Nichols film The Graduate. The resulting single, “Mrs. Robinson”, became a smash hit. Both The Graduate soundtrack and Simon & Garfunkel’s next studio album, Bookends, were major hits on the album chart, with combined total sales in excess of five million copies. Simon and Garfunkel’s fifth and final studio album, Bridge over Troubled Water (1970), reached number one in the US album charts in January 1970 and became one of the most successful albums of all time.

Hoyt Axton and Tom Rush

Davis lured artists Hoyt Axton and Tom Rush to Columbia in 1969, and both were given what was known as “the pop treatment” by the label. Hoyt Axton had been a folk/blues singer-songwriter since the early 1960s, when he made several albums for Horizon, then Vee-Jay. By the time he joined Columbia, he had mixed successful pop songs like “Greenback Dollar,” with hard rock songs for Steppenwolf, such as “The Pusher”, which was used in the film Easy Rider in the same year. When he landed at Columbia, his album My Griffin Is Gone was described as “the poster child for ‘overproduced,’ full of all kinds of instruments and even strings.” After that album, Axton left and joined Capitol Records, where his next albums contained “Joy to the World” and “Never Been to Spain,” which became hits for Three Dog Night on Dunhill. Axton eventually became a country singer, and founded his own record label, Jeremiah.

Tom Rush had always been the “storyteller” or “balladeer” type of folk artist, before and after his stint with Columbia, to which Rush was lured from Elektra. As with Axton, Rush was given “the treatment” on his self-titled Columbia debut. The multitude of instruments added to his usual solo guitar were all done “tastefully”, of course, but was not really on par with Rush’s audience expectations. Eventually, Rush returned to his usual sound (which he applied to his next three albums for Columbia) and has been playing to appreciative audiences ever since.

The 1970s

Catalog numbers

The Columbia album series began in 1951 with album GL-500 (CL-500) and reached an awkward milestone in 1970, when the stereo numbering sequence reached CS-9999, assigned to the Patti Page album Honey Come Back. This presented a catalog numbering system challenge; Columbia had for 13 years used a four-digit catalog number, and CS-10000 seemed cumbersome. Temporarily, they settled on CS-1000 instead, preserving the four-digit catalog number; however, they were re-using catalog numbers used in 1957-58, even if the prefix was now different. In July, 1970, the cataloging department implemented a new system altogether, combining all their labels into one consolidated catalog numbering system starting with 30000, with the prefix letter indicating which label it was. The first CBS album released under the new system was The Elvin Bishop Group’s self-titled album on Fillmore Records, assigned with 30001, while the first actual Columbia release under the system was Herschel Bernardi’s Show Stopper, assigned with C 30004. The highest catalog number released in the old system was CS-1069, assigned to The Sesame Street Book and Record. Chronologically, Columbia issued at least one album in this series in August, but by that time the CBS Consolidated 30000 series, which started issuing albums in July with the new label design, was well underway, having issued nearly 100 albums. The system was later expanded with even more prefix letters, which continued until 2005.

Quadraphonics

In September 1970, under the guidance of Clive Davis, Columbia Records entered the West Coast rock market, opening a state-of-the art recording studio (which was located at 827 Folsom St. in San Francisco and later morphed into the Automatt) and establishing an A&R head and office in San Francisco at Fisherman’s Wharf, headed by George Daly, a producer and artist for Monument Records (who inked a distribution deal with Columbia at the time) and a former bandmate of Nils Lofgren and Roy Buchanan. The recording studio operated under CBS until 1978.

During the early 1970s, Columbia began recording in a four-channel process called quadraphonic, using the “SQ” (Stereo Quadraphonic) standard that used an electronic encoding process that could be decoded by special amplifiers and then played through four speakers, with each speaker placed in the corner of a room. Remarkably, RCA countered with another quadraphonic process that required a special cartridge to play the “discrete” recordings for four-channel playback. Both Columbia and RCA’s quadraphonic records could be played on conventional stereo equipment. Although the Columbia process required less equipment and was quite effective, many were confused by the competing systems and sales of both Columbia’s matrix recordings and RCA’s discrete recordings were disappointing. A few other companies also issued some matrix recordings for a few years. Quadraphonic recording was used by both classical artists, including Leonard Bernstein and Pierre Boulez, and popular artists such as Electric Light Orchestra, Billy Joel, Pink Floyd, Johnny Cash, Barbra Streisand, Ray Conniff, Carlos Santana, Herbie Hancock, The Clash and Blue Öyster Cult. Columbia even released a soundtrack album of the movie version of Funny Girl in quadraphonic. Many of these recordings were later remastered and released in Dolby surround sound on CD.

Yetnikoff becomes president

In 1975, Walter Yetnikoff was promoted to become President of Columbia Records, and his vacated position as President of CBS Records International was filled by Dick Asher. At this point, according to music historian Frederic Dannen, the shy and introverted Yetnikoff began to transform his personality, “wild, menacing, crude, and above all, very loud.” In Dannen’s view, Yetnikoff was probably over-compensating for his naturally sensitive and generous personality, and that he had little hope of being recognized as a “record man” because he was tone-deaf, so he instead determined to become a “colorful character”.Yetnikoff soon became notorious for his violent temper and regular tantrums: “He shattered glassware, spewed a mixture of Yiddish and barnyard epithets, and had people physically ejected from the CBS building.”

In 1976, Columbia Records of Canada was renamed CBS Records Canada Ltd. The Columbia label continued to be used by CBS Canada, but the CBS label was introduced for French-language recordings. On May 5, 1979, Columbia Masterworks began digital recording in a recording session of Stravinsky’s Petrouchka by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Zubin Mehta, in New York.

Dick Asher vs “The Network”

CBS Records had a popular roster of musicians. It distributed Philadelphia International Records, Blue Sky Records, the Isley Brothers’ T-Neck Records and Monument Records (from 1971 to 1976). But the music industry was in financial decline. Total sales fell by 11%, the biggest drop since World War II. In 1979 CBS had a pre-tax income of $51 million and sales of over $1 billion. The label laid off hundreds of employees.

To deal with the crisis, CEO John Backe promoted Dick Asher from Vice President of Business Affairs to Deputy President. Charged with cutting costs and restoring profits, Asher was reportedly reluctant to take on the role. He was worried that Yetnikoff would resent his promotion. But Backe had confidence in Asher’s experience. In 1972 Asher had turned the British division of CBS from loss to profit. Backe considered him to be honest and trustworthy, and he appealed to Asher’s loyalty to the company. Employees at CBS thought Asher was a bore and an interloper. He cut back on expenses and on perks like limousines and restaurants. His relationship with Yetnikoff deteriorated.

Asher became increasingly concerned about the huge and rapidly growing cost of hiring independent agents, who were paid to promote new singles to radio station program directors. “Indies” had been used by record labels for many years to promote new releases, but as he methodically delved into CBS Records’ expenses, Asher was dismayed to discover that hiring these independent promoters was now costing CBS alone as much as $10 million per year. When Asher took over CBS’ UK division in 1972, a freelance promoter might only charge $100 per week, but by 1979 the top American independent promoters had organized themselves into a loose collective known as “The Network”, and their fees were now running into the tens millions of dollars per year, Music historian Frederic Dannen estimates that by 1980 the major labels were paying anywhere from to $100,000 to $300,000 per song to the “Network” promoters, and that it was costing the industry as whole as much as $80 million annually.

During this period, Columbia scored a Top 40 hit with the Pink Floyd single “Another Brick In The Wall”, and its parent album The Wall would spend four months at No. 1 on the Billboard LP chart in early 1980, but few in the industry knew that Dick Asher was in fact using the single as a covert experiment to test the extent of the pernicious influence of The Network – by not paying them to promote the new Pink Floyd single. The results were immediate and deeply troubling – not one of the major radio stations in Los Angeles would program the record, despite the fact that the group was in town, performing sell-out shows to rave reviews. Asher was already worried about the growing power of The Network, and the fact it operated entirely outside the control of the label, but he was profoundly dismayed to realize that “The Network” was in effect a huge extortion racket, and that the operation could well be linked to organized crime – a concern vehemently dismissed by Yetnikoff, who resolutely defended the “indies” and declared them to be “mensches”. But Dick Asher now knew that The Network’s real power lay in their ability to prevent records from being picked up by radio, and as an experienced media lawyer and a loyal CBS employee, he was also acutely aware that this could become a new payola scandal which had the potential to engulf the entire CBS corporation, and that the Federal Communications Commission could even revoke CBS’ all-important broadcast licenses if the corporation was found to be involved in any illegality.