British Invasion

The British Invasion was a phenomenon that occurred in the mid-1960s when rock and pop music acts from the United Kingdom, as well as other aspects of British culture, became popular in the United States, and significant to the rising “counterculture” on both sides of the Atlantic. Pop and rock groups such as the Beatles, the Dave Clark Five, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, Herman’s Hermits, the Animals, and the Who were at the forefront of the invasion.

The rebellious tone and image of US rock and roll and blues musicians became popular with British youth in the late 1950s. While early commercial attempts to replicate American rock and roll mostly failed, the trad jazz–inspired skiffle craze, with its ‘do it yourself’ attitude, was the starting point of several British Billboard singles.

Young British groups started to combine various British and American styles, in different parts of the U.K., such as a movement in Liverpool during 1962 in what became known as Merseybeat, hence the “beat boom”. That same year featured the first three acts with British roots to reach the Hot 100’s summit, including the Tornados’ instrumental “Telstar”, written and produced by Joe Meek, becoming the first record by a British group to reach number one on the US Hot 100.

Some observers have noted that US teenagers were growing tired of singles-oriented pop acts like Fabian. The Mods and Rockers, two youth “gangs” in mid-1960s Britain, also had an impact in British Invasion music. Bands with a Mod aesthetic became the most popular, but bands able to balance both (e.g. the Beatles) were also successful.

On October 29, 1963, The Washington Post published the first story in the USA about the frenzy surrounding the rock group the Beatles in the United Kingdom.

The Beatles’ November 4 Royal Variety Performance in front of the Queen Mother sparked music industry and media interest in the group. During November a number of major American print outlets and two network television evening programs published and broadcast stories on the phenomenon that became known as “Beatlemania”.

On December 10 CBS Evening News anchor Walter Cronkite, looking for something positive to report, re-ran a Beatlemania story that originally had aired on the 22 November 1963 edition of the CBS Morning News with Mike Wallace but shelved that night because of the assassination of US President John Kennedy.

After seeing the report, 15-year-old Marsha Albert of Silver Spring, Maryland, wrote a letter the following day to disc jockey Carroll James at radio station WWDC asking, “Why can’t we have music like that here in America?”

On December 17 James had Miss Albert introduce “I Want to Hold Your Hand” live on the air. WWDC’s phones lit up, and Washington, D.C., area record stores were flooded with requests for a record they did not have in stock.

James sent the record to other disc jockeys around the country sparking similar reaction.

On December 29 The Baltimore Sun, reflecting the dismissive view of most adults, editorialized, “America had better take thought as to how it will deal with the invasion. Indeed a restrained ‘Beatles go home’ might be just the thing.”

That comment proved prophetic. In the next year alone, the Beatles would have 30 different listings on the Hot 100.

On January 3, 1964, The Jack Paar Program ran Beatles concert footage licensed from the BBC “as a joke” but watched by 30 million viewers. While this piece was largely forgotten, Beatles producer George Martin has said it “aroused the kids’ curiosity”.

In the middle of January 1964, “I Want to Hold Your Hand” appeared suddenly, then vaulted to the top of nearly every top 40 music survey in the United States, launching the Fab Four’s sustained, massive output. “I Want to Hold Your Hand” ascended to number one on the January 25, 1964, edition of Cash Box magazine (on sale January 18) and the February 1, 1964, edition of the Hot 100.

On February 7, 1964, the CBS Evening News ran a story about the Beatles’ United States arrival that afternoon in which the correspondent said, “The British Invasion this time goes by the code name Beatlemania.

Two days later (Sunday, February 9) they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. Nielsen Ratings estimated that 45 percent of US television viewers that night saw their appearance

According to Michael Ross, “It is somewhat ironic that the biggest moment in the history of popular music was first experienced in the US as a television event.” The Ed Sullivan Show had for some time been a “comfortable hearth-and-slippers experience.”

Not many of the 73 million viewers watching in February 1964 would fully understand what impact the band they were watching would have.

The Beatles soon incited contrasting reactions and, in the process, generated more novelty records than anyone – at least 200 during their 1964-1965 takeover and many more later (during Paul’s “death” hoax, their break-up, etc.).

Among the many reactions, favoring the hysteria, British girl group The Carefrees’ “We Love You Beatles” (#39 on 11 April 1964) and, on Tuff Records, the Patty Cakes’ “I Understand Them”, subtitled “A Love Song to the Beatles”.

Disapproving the pandemonium, American group the Four Preps’ “A Letter to the Beatles” (#85 on 4 April 1964) and American comedian Allan Sherman’s “Pop Hates the Beatles” (in reaction to the Beatles’ “Pop Go the Beatles”).

On April 4, the Beatles held the top five positions on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, and to date no other act has simultaneously held even the top three.

On April 4, the Beatles held the top five positions on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, and to date no other act has simultaneously held even the top three.

The group’s massive chart success, which included at least two of their singles holding the top spot on the Hot 100 during each of the seven consecutive years starting with 1964, continued until they broke up in 1970.

One week after the Beatles entered the Hot 100 for the first time, Dusty Springfield, having launched a solo career after her participation in the Springfields, became the next British act to reach the Hot 100, with “I Only Want to Be with You.” Released in late 1963, this successful hit peaked at number 12 on the Hot 100 right around the time The Beatles began to dominate the U.S. airwaves. She soon followed up with several other hits, becoming what AllMusic described as “the finest white soul singer of her era.”

On the Hot 100, Dusty’s solo career lasted almost as long, albeit with little more than one quarter of the hits, as the Beatles’ group career before their breakup. During the next two years or so, Peter and Gordon, the Animals, Manfred Mann, Petula Clark, Freddie and the Dreamers, Wayne Fontana and the Mindbenders, Herman’s Hermits, the Rolling Stones, the Dave Clark Five, the Troggs, Donovan, and Lulu in 1967, would have one or more number one singles in the US. Other Invasion acts included the Searchers, Billy J. Kramer, the Bachelors, Chad & Jeremy, Gerry and the Pacemakers, the Honeycombs, Them (and later its lead singer, Van Morrison), Tom Jones, the Yardbirds (whose guitarist Jimmy Page would later form Led Zeppelin), the Spencer Davis Group, the Small Faces, and numerous others.

The Kinks, although considered part of the Invasion, initially failed to capitalize on their success in the US after their first three hits reached the Hot 100’s top 10 (in part due to a ban by the American Federation of Musicians) before resurfacing in 1970 with “Lola” and in 1983 with their biggest hit, “Come Dancing”. On May 8, 1965, the British Commonwealth came closer than it ever had or would to a clean sweep of a weekly Hot 100’s Top 10, lacking only a hit at number two instead of “Count Me In” by the US group Gary Lewis & the Playboys. That same year, half of the 26 Billboard Hot 100 chart toppers (counting the Beatles’ “I Feel Fine” carrying over from 1964) belonged to British acts.

The British trend would continue into 1966 and beyond. British Invasion acts also dominated the music charts at home in the United Kingdom.

As 1965 approached another wave of British Invasion artists emerged which consisted usually of either of groups playing in a more pop style, such as the Hollies or the Zombies or with a harder-driving, blues-based approach such as the Who. The musical style of British Invasion artists, such as the Beatles, had been influenced by earlier US rock ‘n’ roll, a genre which had lost some popularity and appeal by the time of the Invasion.

However, a subsequent handful of white British performers, particularly the Rolling Stones and the Animals, would appeal to a more ‘outsider’ demographic, essentially reviving and popularizing, for young people at least, a musical genre rooted in the blues, rhythm and black culture, which had been largely ignored or rejected when performed by black US artists in the 1950s.

Such bands were sometimes perceived by American parents and elders as rebellious and unwholesome. This image marked them as separate from artists such as the Beatles, who had become a more acceptable, parent-friendly pop group. The Rolling Stones would become the biggest band other than the Beatles to come out of the British Invasion,[60] topping the Hot 100 eight times.

Sometimes, there would be a clash between the two styles of the British Invasion, the polished pop acts and the grittier blues-based acts due to the expectations set by the Beatles. Eric Burdon of the Animals said “They dressed us up in the most strange costumes.

They were even gonna bring a choreographer to show us how to move on stage. I mean, it was ridiculous. It was something that was so far away from our nature and, um, yeah we were just pushed around and told, ‘When you arrive in America, don’t mention the [Vietnam] war! You can’t talk about the war.’ We felt like we were being gagged.”

“Freakbeat” is a term sometimes given to certain British Invasion acts closely associated with the mod scene during the Swinging London period, particularly harder-driving British blues bands of the era, that often remained obscure to US listeners, and who are sometimes seen as counterparts to the garage rock bands in America. Certain acts, such as the Pretty Things and the Creation, had a certain degree of chart success in the UK and are often considered exemplars of the form.

The emergence of a relatively homogeneous worldwide “rock” music style marking the end of the “invasion” occurred in 1967, but not without one final comment from America, when one-hit wonder The Rose Garden’s “Next Plane to London” peaked at #17 during the last week of that year

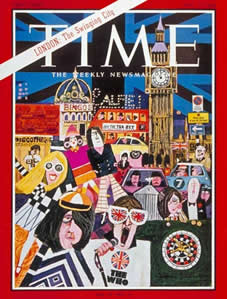

Outside of music, other aspects of British arts became popular in the US during this period and led US media to proclaim the United Kingdom as the center of music and fashion.

Outside of music, other aspects of British arts became popular in the US during this period and led US media to proclaim the United Kingdom as the center of music and fashion.

The Beatles movie A Hard Day’s Night marked the group’s entrance into film.

Mary Poppins, released on August 27, 1964, and starring English actress Julie Andrews as the titular character, became the most Oscar-winning and Oscar-nominated Disney film in history, and My Fair Lady, released on December 25, 1964, starring British actress Audrey Hepburn as Cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle, won eight Academy Awards.

Besides the Bond series which commenced with Sean Connery as James Bond in 1962, films with a British sensibility such as the “Angry Young Men” genre, What’s New Pussycat? and Alfie styled London Theatre. A new wave of actors such as Peter O’Toole and Michael Caine intrigued US audiences.

Four of the decade’s Academy Award winners for best picture were British productions, with the epic Lawrence of Arabia, starring O’Toole as British army officer T. E. Lawrence, winning seven Oscars in 1963.

Fashion and image marked the Beatles out from their earlier US rock and roll counterparts. Their distinctive, uniform style “challenged the clothing style of conventional US males,” just as their music challenged the earlier conventions of the rock and roll genre. “Mod” fashions, such as the mini skirt from “Swinging London” designers such as Mary Quant and worn by early supermodels Twiggy, Jean Shrimpton and other models, were popular worldwide.

John Crosby wrote, “The English girl has an enthusiasm that American men find utterly captivating. I’d like to import the whole Chelsea girl with her ‘life is fabulous’ philosophy to America with instructions to bore from within..

Even while longstanding styles remained popular, US teens and young adults started to dress “hipper”. The evolution of the styles of the British Invasion bands also showed in US culture, as some bands went from more clean cut to being more hippies

In anticipation of the 2013 50th anniversary of the British Invasion, comics such as Nowhere Men, which are loosely based on the events of it, have gained popularity.

The British Invasion had a profound impact on popular music, internationalizing the production of rock and roll, establishing the British popular music industry as a viable center of musical creativity,[80] and opening the door for subsequent British performers to achieve international success.

In America the Invasion arguably spelled the end of the popularity of instrumental surf music,[81] pre-Motown vocal girl groups, the folk revival (which adapted by evolving into folk rock), and (for a time) the teen idols that had dominated the American charts in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Television shows that featured uniquely American styles of music, such as Sing Along with Mitch and Hootenanny, were quickly canceled and replaced with shows such as Shindig! and Hullabaloo that were better positioned to play the new British hits, and segments of the new shows were taped in England.

It dented the careers of established R&B acts like Chubby Checker and temporarily derailed the chart success of certain surviving rock and roll acts, including Ricky Nelson, Fats Domino, and Elvis Presley. It prompted many existing garage rock bands to adopt a sound with a British Invasion inflection and inspired many other groups to form, creating a scene from which many major American acts of the next decade would emerge.

The British Invasion also played a major part in the rise of a distinct genre of rock music and cemented the primacy of the rock group, based around guitars and drums and producing their own material as singer-songwriters.

Though many of the acts associated with the invasion did not survive its end, many others would become icons of rock music. The claim that British beat bands were not radically different from US groups like the Beach Boys and damaged the careers of African-American and female artists was made about the Invasion. However, the Motown sound, exemplified by The Supremes, The Temptations, and the Four Tops, each securing its first top 20 record during the Invasion’s first year of 1964 and following up with many other top 20 records, besides the constant or even accelerating output of The Miracles, Gladys Knight & the Pips, Marvin Gaye, Martha & The Vandellas, and Stevie Wonder, actually increased in popularity during that time.

Other US groups also demonstrated a similar sound to the British Invasion artists and in turn highlighted how the British ‘sound’ was not in itself a wholly new or original one.[91] Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, for example, acknowledged the debt that American artists owed to British musicians, such as The Searchers, but that “they were using folk music licks that I was using anyway. So it’s not that big a rip-off.”

The US sunshine pop group the Buckinghams and the Beatles-influenced US Tex-Mex act the Sir Douglas Quintet adopted British-sounding names, and San Francisco’s Beau Brummels took their name from the same-named English dandy. Roger Miller had a 1965 hit record with a song titled “England Swings”.[96] Englishman Geoff Stephens (or John Carter) reciprocated the gesture a la Rudy Vallée a year later in the New Vaudeville Band’s “Winchester Cathedral”.

Even as recently as 2003, “Shanghai Knights” made the latter two tunes memorable once again, in London scenes. Anticipating the Bay City Rollers by more than a decade, two British acts that reached the Hot 100’s top 20 gave a tip of the hat to America: Billy J. Kramer with the Dakotas and the Nashville Teens.

The British Invasion also drew a backlash from some American bands, e.g., Paul Revere & the Raiders and New Colony Six dressed in Revolutionary War uniforms, and Gary Puckett & The Union Gap donned Civil War uniforms. Garage rock act the Barbarians’ “Are You a Boy or Are You a Girl” contained the lyrics “You’re either a girl, or you come from Liverpool” and “You can dance like a female monkey, but you swim like a stone, Yeah, a Rolling Stone.”

In Australia, the success of the Seekers and the Easybeats (the latter a band formed mostly of British emigrants) closely paralleled that of the British Invasion. The Seekers had two Hot 100 top 5 hits during the British Invasion, the #4 hit “I’ll Never Find Another You” in May 1965 and the #2 hit “Georgy Girl” in February 1967.

In Australia, the success of the Seekers and the Easybeats (the latter a band formed mostly of British emigrants) closely paralleled that of the British Invasion. The Seekers had two Hot 100 top 5 hits during the British Invasion, the #4 hit “I’ll Never Find Another You” in May 1965 and the #2 hit “Georgy Girl” in February 1967.

The Easybeats drew heavily on the British Invasion sound and had one hit in the United States during the British Invasion, the #16 hit “Friday on My Mind” in May 1967.

According to Robert J. Thompson, director of the Center for the Study of Popular Television at Syracuse University, the British invasion pushed the counterculture into the mainstream.

It’s unclear when the British Invasion can be said to have “ended,” if it ever ended at all. American bands regained prominence on the charts in the late 1960s in the face of changing cultural norms; even so, British bands continued to have consistent success alongside their American counterparts on the U.S. charts throughout the decade. Into the 1970s, bands such as Badfinger,

The Raspberries, and Sweet were playing a heavily British Invasion-influenced style deemed power pop. In 1978 two rock magazines wrote cover stories about power pop and championed the genre as a savior to both the new wave and the direct simplicity of the way rock used to be.

New wave power pop not only brought back the sounds but the fashions, be it the mod style of the Jam or the skinny ties of the burgeoning Los Angeles scene. Several of these groups were commercially successful, most notably the Knack, whose My Sharona was the number 1 U.S. single of 1979. A backlash against the Knack and power pop ensued, but the genre over the years has continued to have a cult following with occasional periods of modest success. Another wave of British artists, dubbed the “Second British Invasion”, became popular in the 1980s as music video showcases began to appear on American television.