1950s

(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock: Bill Haley and His Comets

is a rock and roll song in the 12-bar blues format written by Max C. Freedman and James E. Myers (the latter under the pseudonym “Jimmy De Knight”) in 1952.

is a rock and roll song in the 12-bar blues format written by Max C. Freedman and James E. Myers (the latter under the pseudonym “Jimmy De Knight”) in 1952.

The best-known and most successful rendition was recorded by Bill Haley & His Comets in 1954 for American Decca. It was a number one single on both the United States and United Kingdom charts and also re-entered the UK Singles Chart in the 1960s and 1970s.

It was not the first rock and roll record, nor was it the first successful record of the genre (Bill Haley had American chart success with “Crazy Man, Crazy” in 1953, and in 1954, “Shake, Rattle and Roll” sung by Big Joe Turner reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart).

It was not the first rock and roll record, nor was it the first successful record of the genre (Bill Haley had American chart success with “Crazy Man, Crazy” in 1953, and in 1954, “Shake, Rattle and Roll” sung by Big Joe Turner reached No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart).

Haley’s recording nevertheless became an anthem for rebellious 1950s youth and is widely considered to be the song that, more than any other, brought rock and roll into mainstream culture around the world.

The song is ranked No. 158 on the Rolling Stone magazine’s list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZgdufzXvjqw[/embedyt]

Cry: Johnnie Ray

is the title of a 1951 popular song written by Churchill Kohlman. The song was first recorded by Ruth Casey on the Cadillac label. The biggest hit version was recorded in New York City by Johnnie Ray and The Four Lads on October 16, 1951. Johnnie Ray recording was released on Columbia Records subsidiary label Okeh Records as catalog number Okeh 6840. It was a No.1 hit on the Billboard magazine chart that year, and one side of one of the biggest two-sided hits, as the flip side, “The Little White Cloud That Cried,” reached No.2 on the Billboard chart. This recording also hit number one on the R&B Best Sellers lists and the flip side, “The Little White Cloud that Cried,” peaked at number six. When the single started to crack the charts the single was released on Columbia Records catalog number Co 39659.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lIxl_ISz1Ag[/embedyt]

Sh-Boom: The Crew Cuts

is an early doo-wop song. It was written by James Keyes, Claude Feaster, Carl Feaster, Floyd F. McRae, and James Edwards, members of the R&B vocal group the Chords and published in 1954. It was a U.S. top ten hit that year for both the Chords (who first recorded the song) and the Crew-Cuts.

The song was first recorded on Atlantic Records’ subsidiary label Cat Records by the Chords on March 15, 1954 and would be their only hit song. “Sh-Boom” reached #2 on the Billboard R&B charts and peaked at #9 on the pop charts. It is sometimes considered to be the first doo-wop or rock ‘n’ roll record to reach the top ten on the pop charts (as opposed to the R&B charts). This version was ranked #215 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time and is the group’s only song on the list.

A more traditional version was made by a Canadian group, the Crew-Cuts (with the David Carroll Orchestra), for Mercury Records and was #1 on the Billboard charts for nine weeks during August and September 1954. The single first entered the charts on July 30, 1954 and stayed for 20 weeks. The Crew-Cuts performed the song on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town on December 12, 1954. On the Cash Box magazine best-selling record charts, where both versions were combined, the song reached #1.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q9G0-4TWwew[/embedyt]

Mr. Sandman: The Chordettes

is a popular song written by Pat Ballard which was published in 1954 and first recorded in May of that year by Vaughn Monroe & His Orchestra and later that same year by The Chordettes. The song’s lyrics convey a request to “Mr. Sandman” to “bring me a dream” – the traditional association with the folkloric figure, the sandman.

The Chordettes’ recording of the song was released on the Cadence Records label, whose founder, Archie Bleyer, is credited on the disc’s label as percussionist (using his knees) and orchestra conductor. Bleyer’s voice is heard in the third verse, when he says the word “Yes?” The piano is played by Moe Wechsler. Liberace’s name is mentioned for his “wavy hair” and Pagliacci for having a lonely heart (a reference to the opera Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo).

The single reached #1 on the Billboard United States charts and #11 in the United Kingdom charts in 1954. In November 1954, The Four Aces, backed by the Jack Pleis Orchestra, released a version that charted even higher in the UK, reaching #9 and in the same year, a version by Max Bygraves reached #16 in the UK charts. The most successful recording of the song in the UK was by Dickie Valentine, which peaked at #5. On the Cash Box magazine charts in the US, where all versions were combined, the song also reached #1.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VNUgsbKisp8[/embedyt]

My Prayer: The Platters

is a 1939 popular song with music by salon violinist Georges Boulanger and lyrics by Carlos Gomez Barrera and Jimmy Kennedy. It was originally written by Boulanger with the title “Avant de Mourir” in 1926.

is a 1939 popular song with music by salon violinist Georges Boulanger and lyrics by Carlos Gomez Barrera and Jimmy Kennedy. It was originally written by Boulanger with the title “Avant de Mourir” in 1926.

The lyrics for this version were added by Kennedy in 1939.

Glenn Miller recorded the song that year for a number two hit and The Ink Spots’ version featuring Bill Kenny reached number three, as well, that year.

It has been recorded many times since, but the biggest hit version was a doo-wop rendition in 1956 by The Platters, whose single release reached number one on the Billboard Top 100 in the summer, and ranked four for the year.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDlcqhlzDqQ[/embedyt]

The Great Pretender: The Platters

is a popular song recorded by The Platters, with Tony Williams on lead vocals, and released as a single on November 3, 1955. The words and music were written by Buck Ram, the Platters’ manager and producer who was a successful songwriter before moving into producing and management. “The Great Pretender” reached the number one position on both the R&B and pop charts in 1956. It also reached the UK charts peaking at number 5.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FyM8NVl4yBY[/embedyt]

Don’t Be Cruel/Hound Dog: Elvis Presley

“Don’t Be Cruel” is a song recorded by Elvis Presley and written by Otis Blackwell in 1956. It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002. In 2004, it was listed #197 in Rolling Stone’s list of 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. The song is currently ranked as the 173rd greatest song of all time, as well as the sixth best song of 1956, by Acclaimed Music.

“Don’t Be Cruel” is a song recorded by Elvis Presley and written by Otis Blackwell in 1956. It was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002. In 2004, it was listed #197 in Rolling Stone’s list of 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. The song is currently ranked as the 173rd greatest song of all time, as well as the sixth best song of 1956, by Acclaimed Music.

Recording

“Don’t Be Cruel” was the first song that Presley’s song publishers, Hill and Range, brought to him to record. Blackwell was more than happy to give up 50% of the royalties and a co-writing credit to Presley to ensure that the “hottest new singer around covered it”. But unfortunately he had already sold the song for only $25, as he stated in an interview of American Songwriter.

Freddy Bienstock, Presley’s music publisher, gave the following explanation for why Elvis received co-writing credit for songs like “Don’t Be Cruel.” “In the early days Elvis would show dissatisfaction with some lines and he would make alterations, so it wasn’t just what is known as a ‘cut-in’. His name did not appear after the first year.

But if Elvis liked the song, the writers would be offered a guarantee of a million records and they would surrender a third of their royalties to Elvis’.”

Presley recorded the song on July 2, 1956 during an exhaustive recording session at RCA studios in New York City. During this session he also recorded “Hound Dog”, and “Any Way You Want Me”. The song featured Presley’s regular band of Scotty Moore on lead guitar (with Presley usually providing rhythm guitar), Bill Black on bass, D. J. Fontana on drums, and backing vocals from the Jordanaires. The producing credit was given to RCA’s Stephen H. Sholes, although the studio recordings reveal that Presley produced the songs in this session by selecting the song, reworking the arrangement on piano, and insisting on 28 takes before he was satisfied with it. He also ran through 31 takes of “Hound Dog”.

Release

The single was released on July 13, 1956 backed with “Hound Dog”. Within a few weeks “Hound Dog” had risen to #2 on the Pop charts with sales of over one million. Soon after it was overtaken by “Don’t Be Cruel” which took #1 on all three main charts; Pop, Country, and R ‘n’ B. Between them, both songs remained at #1 on the Pop chart for a run of 11 weeks tying it with the 1950 Anton Karas hit “The Third Man Theme” and the 1951/1952 Johnnie Ray hit “Cry” for the longest stay at number one by a single record from late 1950 onward until 1992’s smash “End of the Road” by Boyz II Men. By the end of 1956 it had sold in excess of four million copies. Billboard ranked it as the No. 2 song for 1956.

Presley performed “Don’t Be Cruel” during all three of his appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show in September 1956 and January 1957

“Hound Dog” is a twelve-bar blues song written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Recorded originally by Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton on August 13, 1952, in Los Angeles and released by Peacock Records in late February 1953, “Hound Dog” was Thornton’s only hit record, selling over 500,000 copies, spending 14 weeks in the R&B charts, including seven weeks at #1. Thornton’s recording of “Hound Dog” is listed as one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s “500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll”, and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in February 2013

“Hound Dog” is a twelve-bar blues song written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Recorded originally by Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton on August 13, 1952, in Los Angeles and released by Peacock Records in late February 1953, “Hound Dog” was Thornton’s only hit record, selling over 500,000 copies, spending 14 weeks in the R&B charts, including seven weeks at #1. Thornton’s recording of “Hound Dog” is listed as one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s “500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll”, and was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in February 2013

“Hound Dog” has been recorded more than 250 times. The best-known version of “Hound Dog” is the July 1956 recording by Elvis Presley, which is ranked No. 19 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time; it is also one of the best-selling singles of all time. Presley’s version, which sold about 10 million copies globally, was his best-selling song and “an emblem of the rock ‘n’ roll revolution”. It was simultaneously No. 1 on the US pop, country, and R&B charts in 1956, and it topped the pop chart for 11 weeks — a record that stood for 36 years. Presley’s 1956 RCA recording was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1988, and it is listed as one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s “500 Songs That Shaped Rock and Roll”.

Barry Birnbaum described Elvis Presley’s rendition of “Hound Dog” as “an emblem of the rock ‘n’ roll revolution”. George Plasketes argues that Elvis Presley’s version of “Hound Dog” should not be considered a cover “since [most listeners] … were innocent of Willie Mae Thornton’s original 1953 release”. Michael Coyle asserts that “Hound Dog”, like almost all of Presley’s “covers were all of material whose brief moment in the limelight was over, without the songs having become standards.” While, because of its popularity, Presley’s recording “arguably usurped the original”, Plasketes concludes: “anyone who’s ever heard the Big Mama Thornton original would probably argue otherwise.” Presley was aware of and appreciated Big Mama Thornton’s original recording of “Hound Dog”, and had a copy in his personal record collection. Ron Smith, a schoolfriend of Presley’s, says he remembers Elvis singing along to a version by Tommy Duncan (lead singer for the classic lineup of Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys). According to another schoolmate, Elvis’ favorite r’n’b song was “Bear Cat (the Answer to Hound Dog)” by Rufus Thomas, a hero of Presley’s.

Agreeing with Robert Fink, who claims that “Hound Dog” as performed by Presley was intended as a “witty multiracial piece of sygnifyin’ humor, troping off white overreactions to a black sexual innuendo”, Freya Jarman-Ivens asserts that “Presley’s version of ‘Hound Dog’ started its life as a blackface comedy”, in the manner of Al Jolson, but more especially “African-American performers with a penchant for ‘clowning’ – – Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, and Louis Jordan. It was Freddie Bell and the Bellboys’ performance of the song (with Bell’s amended lyrics) that influenced Presley’s decision to perform, and later record and release, his own version: “Elvis’s version of ‘Hound Dog’ (1956) came about, not as an attempt to cover Thornton’s record, but as an imitation of a parody of her record performed by Freddie Bell and the Bellboys. … The words, the tempo, and the arrangement of Elvis’ ‘Hound Dog’ come not from Thornton’s version of the song, but from the Bellboys’.” According to Rick Coleman, the Bellboys’ version “featured [Dave] Bartholomew’s three-beat Latin riff, which had been heard in Bill Haley’s ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll’.” Just as Haley had borrowed the riff from Bartholomew, Presley borrowed it from Bell and the Bellboys. The Latin riff form that was used in Presley’s “Hound Dog” was known as “Habanera rhythm,” which is a Spanish and African-American musical beat form. After the release of “Hound Dog” by Presley, the Habanera rhythm gained much popularity in American popular music.

Presley’s first appearance in Las Vegas was in the Venus Room of the New Frontier Hotel and Casino from Monday, April 23 through May 6, 1956, as an “extra added attraction”, third on the bill to Freddy Martin and His Orchestra and to comedian Shecky Greene. However, “because of audience dissatisfaction, low attendance, and unsavory behavior by underage fans”, the booking was reduced to one week At that time, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, who had been performing as a resident act in the Silver Queen Bar and Cocktail Lounge in the Sands Casino since 1952, were one of the hottest acts in town. Presley and his band decided to take in their show, and not only enjoyed the show, but also loved their reworking of “Hound Dog”, which was a comedy-burlesque with show-stopping va-va-voom choreography. According to Paul W. Papa: “From the first time Elvis heard this song he was hooked. He went back over and over again until he learned the chords and lyrics.” Presley’s guitarist Scotty Moore recalled: “When we heard them perform that night, we thought the song would be a good one for us to do as comic relief when we were on stage. We loved the way they did it. They had a piano player [Russ Conti] who stood up and played – and the way he did his legs they looked like rubber bands bending back and forth. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller wrote the song for Big Mama Thornton, but Freddie and The Bell Boys had a different set of lyrics. Elvis got his lyrics from those guys. He knew the original lyrics but he didn’t use them”.” When asked about “Hound Dog”, Presley’s drummer D. J. Fontana admitted: “We took that from a band we saw in Vegas, Freddie Bell and the Bellboys. They were doing the song kinda like that. We went out there every night to watch them. He’d say: ‘Let’s go watch that band. It’s a good band!’ That’s where he heard ‘Hound Dog,’ and shortly thereafter he said: ‘Let’s try that song.'”

When asked if Bell had any objections to Presley recording his own version, Bell gave Colonel Tom Parker, Presley’s manager, a copy of his 1955 Teen Records’ recording, hoping that if Presley recorded it, “he might reap some benefit when his own version was released on an album.” According to Bell, “[Parker] promised me that if I gave him the song, the next time Elvis went on tour, I would be the opening act for him—which never happened.” In another interview Bell said: “I hope my career is more than giving ‘Hound Dog’ to Elvis”. In May 1956, two months before Presley’s release, Bell re-recorded the song in a more frantic version for the Mercury label, however it was not released as a single until 1957. It was later included on Bell’s 1957 album, Rock & Roll…All Flavors (Mercury Records MG 20289).

Early performances

Presley first added “Hound Dog” to his live performances at the New Frontier Hotel. Ace Collins indicates that “Far from being the frenetic, hard-driving song that he would eventually record, Elvis’ early live renditions of ‘Hound Dog’ usually moved pretty slowly, with an almost burlesque feel.” Just weeks after they had seen Bell and the Bellboys perform, “Hound Dog” became Elvis and Scotty and Bill’s closing number for the first time on May 15, 1956 at Ellis Auditorium in Memphis, during the Memphis Cotton Festival before an audience of 7,000. Like Bell and the Bellboys, Presley performed the song “as comic relief, basing the lyrics and his ‘gyrations’ … on what he had seen in Vegas.” Presley’s performance, including the lyrics (which he sometimes changed) and the gyrations always got a big reaction. It became the standard closer until the late 1960s. By the spring of 1956, Presley was fast becoming a national phenomenon and teenagers came to his concerts in unprecedented numbers. There were many riots at his early concerts. Scotty Moore recalled: “He’d start out, ‘You ain’t nothin’ but a Hound Dog,’ and they’d just go to pieces. They’d always react the same way. There’d be a riot every time.” Presley’s then manager Bob Neal wrote: “It was almost frightening, the reaction… from teenage boys. So many of them, through some sort of jealousy, would practically hate him.” In Lubbock, Texas, a teenage gang fire-bombed Presley’s car. Some performers became resentful (or resigned to the fact) that Presley going on stage before them would “kill” their own act; he thus rose quickly to top billing. At the two concerts he performed at the 1956 Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show, one hundred National Guardsmen were on hand to prevent crowd trouble. Presley researcher Guillermo F. Perez-Argüello contends that:

Whatever Presley got from hearing Freddy Bell’s version, which was sometime in April of 1956, lasted a couple of months only. In fact he sang it 21 times, live, at concerts and on television, using Bell’s vocal arrangement but which also included his own blues version, at half speed, and only at the end, until he recorded it with what was undeniably, his own arrangement based not just on Scotty Moore’ tremendously modern guitar work but his own rage and disgust at what had taken place the night before, at Steve Allen’ s Tonight show, when he was forced to sing the song to a bassett hound, and dressed in tails while simultaneously [sic.] facing an audience of 40 million. And once he recorded it, it was his version which he chose to deliver, although by the end of 1956, he’d added inflections from the Thornton version as well.”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-eHJ12Vhpyc[/embedyt]

Television performances

Milton Berle Show

Presley first performed “Hound Dog” for a nationwide television audience on The Milton Berle Show on June 5, 1956. It was his second appearance on Berle’s program, and his eighth appearance on national television since his debut on January 28, 1956 on Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey’s Stage Show which was then recorded and broadcast from the CBS-TV studio in New York City. For the first time Presley appeared on national television sans guitar. Berle later told an interviewer that he had told Elvis to leave his guitar backstage. “Let ’em see you, son”, advised Uncle Miltie. By this time, Scotty Moore had added a guitar solo to the song, and D.J. Fontana had added a hot drum roll between verses of the song. However, in performing “Hound Dog” “Elvis sings the first line like Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, who repeat “hound dog” behind the lead singer: Elvis sings “hound dog” and his “second voice” repeats “hound dog.” By the third verse, he sings the phrase like Thornton.” An upbeat version ended abruptly as Presley threw his arm back, then began to vamp at half tempo, “You ain’t-a nuthin’ but a hound dog, cuh-crying all the time. You ain’t never caught a rabbit…” A final wave signaled the band to stop. Elvis pointed threateningly at the audience, and belted out, “You ain’t no friend of mine.” Presley’s movements during the performance were energetic and exaggerated and the reactions of young women in the studio audience were enthusiastic, as shown on the broadcast.

Over 40,000,000 people saw the performance, and the next day, controversy exploded. According to Robert Fink, while “Hound Dog” as performed by Presley was intended as a “witty multiracial piece of signifying’ humor, trooping off white overreactions to a black sexual innuendo, … nobody got the joke. … The display was not taken as parody. ‘Hound Dog’ confirmed mainstream America’s worst fears about rock and roll, and sparked nationwide vituperation; for the first time, Presley … was attacked in the media as a sexual exhibitionist with no musical talent.” This performance of “Hound Dog” “triggers the first controversy of his career. Presley sings his latest single, “Hound Dog,” with all the pelvis-shaking intensity his fans scream for. Television critics across the country slam the performance for its “appalling lack of musicality,” for its “vulgarity” and “animalism.” The Catholic Church takes up the criticism in its weekly organ in a piece headlined “Beware Elvis Presley.” Concerns about juvenile delinquency and the changing moral values of the young find a new target in the popular singer. After Berle’s show, Ed Sullivan, whose variety show is one of television’s most popular, declares that he will never hire Presley. Steve Allen, who has already booked Presley for The Tonight Show, resists pressure from NBC to cancel the performance, promising he will not allow the singer to offend.” Cultural theorist David Shumway wrote, “Berle’s network, NBC, received letters of protest, and the various self-appointed guardians of public morality attacked Elvis in the press.” TV critics began a merciless campaign against Elvis, making statements that he had a “caterwauling voice and nonsense lyrics” and was an “influence on juvenile delinquency” (despite the fact that when he started the movements, most of the audience laughed at it), and began using the sobriquet, “Elvis the Pelvis”.

Steve Allen Show

Elvis next appeared on national television singing “Hound Dog” on The Steve Allen Show on July 1. Steve Allen wrote: “When I booked Elvis, I naturally had no interest in just presenting him vaudeville-style and letting him do his spot as he might in concert. Instead we worked him into the comedy fabric of our program…We certainly didn’t inhibit Elvis’ then-notorious pelvic gyrations, but I think the fact that he had on formal evening attire made him, purely on his own, slightly alter his presentation”. As Allen was notoriously contemptuous of rock ‘n’ roll music and songs such as “Hound Dog”, he smirkingly presented Elvis “with a roll that looks exactly like a large roll of toilet paper with, says Allen, the ‘signatures of eight thousand fans,'” and the singer had to wear a tuxedo while singing an abbreviated version of “Hound Dog” to an actual top hat-wearing Basset Hound. Although by most accounts Presley was a good sport about it, according to Scotty Moore, the next morning they were all angry about their treatment the previous night.

Recording

For 7 hours from 2.00pm on July 2, 1956, the day after the Steve Allen Show performance, Presley recorded “Hound Dog” along with “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Any Way You Want Me” for RCA Victor at RCA’s New York City studio with his regular band of Scotty Moore on lead guitar, Bill Black on bass, D. J. Fontana on drums, and backing vocals from the Jordanaires. Despite its popularity in his live shows, Presley had not planned nor prepared to record “Hound Dog”, but agreed to do so at the insistence of RCA’s assigned producer Steve Sholes, who argued that “‘Hound Dog’ was so identified with Elvis that fans would demand a record of the concert standard.” According to Ace Collins: “Elvis may not have wanted to record ‘Hound Dog’, but he had a definite idea of how he wanted the finished product to sound. Though he usually slowed it down and treated it like a blues number in concert, in the studio Elvis wanted the song to come off as fast and dynamic.”[ While the producing credit was given to Sholes, the studio recordings reveal that Presley produced the songs himself, which is verified by the band members. Gordon Stoker, First Tenor of The Jordanaires, who were chosen to provide backup vocals, recalls: “They had demos on almost everything that Elvis recorded, and we’d take it from the demo. We’d listen to the demo, most of the time, and we’d take it from the demo. We had (Big) Mama Thornton’s record on ‘Hound Dog’, since she had a record on that. After listening to it we actually thought it was awful and couldn’t figure out why Elvis wanted to do that.” However, what Stoker did not realize was that Presley wanted to record the version he saw in Las Vegas by Freddie Bell and the Bellboys that he had been performing since May. As session pianist Emidio “Shorty Long” Vagnoni left to work on a rehearsal for a stage show, Stoker plays piano on this recording of “Hound Dog”. As Stoker was unable to also sing first tenor, “the Jordanaires try to come up with a combined sound as best they can to cover it, and Gordon laughs as he states, ‘That’s one of the worst sounds we ever got on any record!’ However Elvis insists on doing the song, and the results, albeit without Gordon singing tenor, will still do more than please the masses. Gordon also related that Elvis very much knew in his mind what he wanted the final results to be so they didn’t spend a lot of time working out tempos.”[224] In response to journalist Dave Schwensen, who said: “I remember reading an interview a few years ago with Keith Richards from The Rolling Stones, … “He was talking about the second guitar break on the recording of ‘Hound Dog’ and said it sounded like you just took off your guitar, dropped it on the floor and it got the perfect sound. He said he’s never been able to figure out how you did that.”, in 2002 Scotty Moore indicated: “I don’t know either,” … “Ahh … I was actually pissed off to tell’ya the truth.” … “It was just… Sometimes in the studio you do it too many times and you go past that peak. Like three takes before was really the one you should use. That was it. We had done the thing, (“Hound Dog”). I think it was printed somewhere that we did it about forty or sixty … I don’t know, give or take. But if someone was counting it off, just a couple notes and we stop, that’s a take. You know? ‘Take Two.’ But I was frustrated for some reason and in the second solo I just went, BLAH,”

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_BNNqD1Eg0[/embedyt]

Musicologist Robert Fink asserts that “Elvis drove the band through thirty-one takes, slowly fashioning a menacing, rough-trade version quite different than the one they had been performing on the stage.” The result of Presley’s efforts was an “angry hopped-up version” of “Hound Dog”. Citing Presley’s anger at his treatment on the Steve Allen Show the previous evening, Peter Nazareth sees this recording as “revenge on Steve (“you ain’t no friend of mine”) Allen, and as a protest at being censored on national TV.”[229] In analyzing Presley’s recording, Fink asserts that

“Hound Dog” is “notable for an unremitting level of what can only be called rock and roll dissonance: Elvis just shouts, leaving behind almost completely the rich vocal timbres (“romantic lyricism”) and mannerist rhythmic play on added syllables (“boogification”) that Richard Middleton identifies as the cornerstones of his art. Scotty Moore’s guitar is feral: playing rhythm he stays in the lowest register, slashing away at open fifths and hammering the strong beats with bent and distorted pitches; his repetitive breaks are stinging and even, when he begins one chorus in the wrong key, quite literally atonal. … And the Jordanaires, a gospel quartet who would provide wonderfully subtle rhythmic backup on the next song Elvis recorded at the session, ‘Don’t Be Cruel’, are just hanging on for the ride during this one, while drummer D.J. Fontana just goes plumb crazy. Fontana’s machine-gun drumming on this record has become deservedly famous: the only part of his kit consistently audible in the mix is the snare, played so loud and insistently that the RCA engineers just gave up and let his riffs distort into splatters of clipped noise. The overall effect could not be more different from the amuse, relaxed contempt of Big Mama Thornton; it is reminiscent of nothing so much s late 1970s white punk rage – the Ramones, Iggy Pop, the Sex Pistols.

In the end, Presley chose version 28, declaring: “This is the one.” During the day Presley’s manager Colonel Tom Parker told RCA vice president Larry Kananga that “Hound Dog” “may become such a big hit that RCA may have to change its corporate symbol from the ‘Victor Dog’ to the ‘Hound Dog’.”[ After this recording, Presley performed this “angry hopped-up version” of “Hound Dog” in his concerts, and also on his performances on The Ed Sullivan Show on September 9 and October 28, 1956.

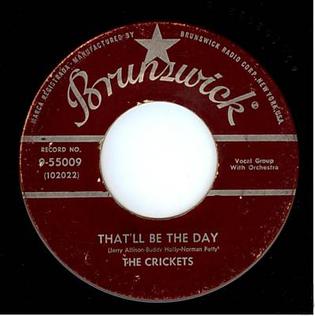

That’ll Be the Day: The Crickets

is a song written by Buddy Holly and Jerry Allison. It was first recorded by Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes in 1956 and was re-recorded in 1957 by Holly and his new band, the Crickets.

is a song written by Buddy Holly and Jerry Allison. It was first recorded by Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes in 1956 and was re-recorded in 1957 by Holly and his new band, the Crickets.

The 1957 recording achieved widespread success. Holly’s producer, Norman Petty, was credited as a co-writer, although he did not contribute to the composition.

Background

In June 1956, Holly, Allison and Sonny Curtis went to see the movie The Searchers, starring John Wayne, in which Wayne repeatedly used the phrase “that’ll be the day”. This line of dialogue inspired the young musicians.

Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes’ version

The song was first recorded by Buddy Holly and the Three Tunes for Decca Records at Bradley’s Barn, in Nashville, on July 22, 1956. Decca, displeased with Holly’s previous two singles, did not issue recordings from this session. After the song was re-recorded by the Crickets in 1957 and became a hit, Decca released the original recording as a single (Decca D30434) on September 2, 1957, with “Rock Around with Ollie Vee” as the B-side. It was also the title track of the 1958 album That’ll Be the Day. Despite Holly’s newfound stardom, the single did not chart.

The Crickets’ version

Holly’s contract with Decca prohibited him from re-recording any of the songs recorded in the 1956 Nashville sessions for five years, even if Decca never released them. To evade this restriction, the producer Norman Petty credited the Crickets as the artist on his re-recording of “That’ll Be the Day” for Brunswick Records. Ironically, Brunswick was a subsidiary of Decca. Once the cat was out of the bag, Decca re-signed Holly to another of its subsidiaries, Coral Records, so he ended up with two recording contracts. Recordings with the Crickets were to be issued by Brunswick, and his solo recordings were to be on Coral.

Holly’s contract with Decca prohibited him from re-recording any of the songs recorded in the 1956 Nashville sessions for five years, even if Decca never released them. To evade this restriction, the producer Norman Petty credited the Crickets as the artist on his re-recording of “That’ll Be the Day” for Brunswick Records. Ironically, Brunswick was a subsidiary of Decca. Once the cat was out of the bag, Decca re-signed Holly to another of its subsidiaries, Coral Records, so he ended up with two recording contracts. Recordings with the Crickets were to be issued by Brunswick, and his solo recordings were to be on Coral.

The second recording of the song was made on February 25, 1957, seven months after the first, at the Norman Petty studios in Clovis, New Mexico, and issued by Brunswick on May 27, 1957. This version is on the debut album by the Crickets, The “Chirping” Crickets, issued on November 27, 1957.

The Brunswick recording of “That’ll Be the Day” is considered a classic of rock and roll. It was ranked number 39 on Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Songs of All Time”.

The final phrase of the song’s lyrics — predicting “that’ll be the day-ay-ay when I die” — seemed eerily prescient after Holly, then only 22, and fellow singers Ritchie Valens and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson were killed in a plane crash on Feb. 3, 1959, a tragically iconic event later memorialized as The Day the Music Died.

Charts and certification

The Brunswick single was a number-one hit on Billboard magazine’s Best Sellers in Stores chart in 1957. It went to number two on Billboard’s R&B singles chart. The song peaked at number 1 in the UK Singles Chart in November 1957 and stayed in that position for three weeks.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcveTkoahXU[/embedyt]

At the Hop: Danny and the Juniors

is a rock and roll/doo-wop song written by Artie Singer, John Medora, and David White and originally released by Danny & the Juniors. The song was released in the fall of 1957, and reached number one on the US charts on January 6, 1958, thus becoming one of the top-selling singles of 1958.

is a rock and roll/doo-wop song written by Artie Singer, John Medora, and David White and originally released by Danny & the Juniors. The song was released in the fall of 1957, and reached number one on the US charts on January 6, 1958, thus becoming one of the top-selling singles of 1958.

“At the Hop” also hit number one on the R&B Best Sellers list. Somewhat more surprisingly, the record reached #3 on the Music Vendor country charts. It was also a big hit elsewhere, which included the group enjoying a number 3 placing with the song on the UK charts.

Background

The song was written by White, Medora, and Singer in 1957, when Danny & the Juniors were still called The Juvenairs. Initially called “Do the Bop”, the song was heard by Dick Clark, who suggested they change its name. After performing the song on Clark’s show American Bandstand, it gained popularity and went to the top of the US charts, remaining at number one for five weeks.

The song describes the scene at a record hop, particularly the dances being performed and the interaction with the disc jockey host.

A sample of the song’s lyrics (contemporary popular dances in italics):

You can rock it you can roll it

Do the stomp and even stroll it

At the hop.

When the record starts spinnin’

You chalypso and you chicken at the hop

Do the dance sensation that is sweepin’ the nation

at the hop

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F3SrtN6tMyg[/embedyt]

Honeycomb: Jimmie Rodgers

is a popular song written by Bob Merrill in 1954. The best-selling version was recorded by Jimmie Rodgers and charted at number one on the Billboard Top 100 in 1957. “Honeycomb” also reached number one on the R&B Best Sellers chart and number seven on the Country & Western Best Sellers in Stores chart. It became a gold record. The song is referenced in the McGuire Sisters hit song “Sugartime”, when the soloist sings the line: “Just be my “Honeycomb” which is echoed by the other sisters and the male chorus. (Honeycomb, Honeycomb, Honeycomb.)

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zHa2fMpMBss[/embedyt]

All I Have to Do is Dream: The Everly Brothers

is a popular song made famous by the Everly Brothers, written by Boudleaux Bryant of the husband and wife songwriting team Felice and Boudleaux Bryant,[2] and published in 1958. The song is ranked No. 141 on the Rolling Stone magazine’s list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

By far the best-known version was recorded by The Everly Brothers and released as a single in April 1958. It had been recorded by The Everly Brothers live in just two takes on March 6, 1958, and features Chet Atkins on guitar. It was the only single ever to be at No. 1 on all of Billboard‘ singles charts simultaneously, on June 2, 1958. It first reached No. 1 on the “Most played by Jockeys” and “Top 100” charts on May 19, 1958, and remained there for five and three weeks, respectively; with the August 1958 introduction of the Billboard Hot 100 chart, the song ended the year at No. 2. “All I Have to Do Is Dream” also hit No.1 on the R&B chart as well as becoming The Everly Brothers’ third chart topper on the country chart. The Everly Brothers briefly returned to the Hot 100 in 1961 with this song. It entered the U.K. Singles Chart on May 23, 1958, reaching the No. 1 position on July 4 and remaining there for seven weeks (including one week as a joint No. 1 with Vic Damone’s “On the Street Where You Live”), spending 21 weeks on the chart.

The song has also featured on several notable lists of the best songs or singles of all time, including Q‘s 1001 best songs ever in 2003. It was named one of the “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll” by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and received the Grammy Hall of Fame Award in 2004.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxWZT0PXkGg[/embedyt]

Poor Little Fool: Ricky Nelson

is a rock and roll song written by Sharon Sheeley and first recorded by Ricky Nelson in 1958.

Sheeley wrote the song when she was fifteen years old. She had met Elvis Presley, and he encouraged her to write. It was based on her disappointment following a short-lived relationship with a member of a popular singing duo. Sheeley sought Ricky Nelson to record the tune. She drove to his house, and claimed her car had broken down. He came to her aid, and she sprang the song on him. Her version was at a much faster tempo than his recording.

The song was recorded by Ricky Nelson on April 17, 1958, and released on Imperial Records through its catalog number: 5528. It was the first number-one song on Billboard magazine’s then-new Hot 100 chart, replacing the magazine’s Jockeys and Top 100 charts. It spent two weeks at the number-one spot. It also reached the top ten on the Billboard Country and Rhythm and Blues charts. Following its success, Sheeley worked with Eddie Cochran.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R12H8QWnwvE[/embedyt]

Mack the Knife: Bobby Darin

is a song composed by Kurt Weill with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht for their music drama Die Dreigroschenoper, or, as it is known in English, The Threepenny Opera. It premiered in Berlin in 1928 at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. The song has become a popular standard recorded by many artists, including a US and UK number one hit for Bobby Darin in 1959.

is a song composed by Kurt Weill with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht for their music drama Die Dreigroschenoper, or, as it is known in English, The Threepenny Opera. It premiered in Berlin in 1928 at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. The song has become a popular standard recorded by many artists, including a US and UK number one hit for Bobby Darin in 1959.

“Mack the Knife” was introduced to the United States hit parade by Louis Armstrong in 1956, but the song is most closely associated with Bobby Darin, who recorded his version at Fulton Studios on West 40th Street, New York City, on December 19, 1958 (with Tom Dowd engineering the recording). Even though Darin was reluctant to release the song as a single, in 1959 it reached number one on the Billboard Hot 100 and number six on the Black Singles chart, and earned him a Grammy Award for Record of the Year. Dick Clark had advised Darin not to record the song because of the perception that, having come from an opera, it would not appeal to the rock and roll audience. In subsequent years, Clark recounted the story with good humor. Frank Sinatra, who recorded the song with Quincy Jones on his L.A. Is My Lady album, called Darin’s the “definitive” version. Billboard ranked this version as the No. 2 song for 1959. Darin’s version was No. 3 on Billboard’s All Time Top 100. In 2003, the Darin version was ranked #251 on Rolling Stone‘s “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” list. On BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, pop mogul Simon Cowell named “Mack the Knife” the best song ever written. Darin’s version of the song was featured in the movie What Women Want. Both Armstrong and Darin’s versions were inducted by the Library of Congress in the National Recording Registry in 2016.[10]

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GSGc0bx-kKM[/embedyt]

1960’s

Save the Last Dance for Me: The Drifters

is the title of a popular song written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, first recorded in 1960 by The Drifters, with Ben E. King on lead vocals. In a 1990 interview, songwriter Doc Pomus tells the story of the song being recorded by the Drifters and originally designated as the B-side of the record. He credits Dick Clark with turning the record over and realizing “Save The Last Dance” was the stronger song. The Drifters’ version of the song, released a few months after Ben E. King left the group, would go on to spend three non-consecutive weeks at #1 on the U.S. pop chart, in addition to logging one week atop the U.S. R&B chart. In the UK The Drifters’ recording reached #2 in December 1960. This single was produced by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, two noted American music producers who at the time had an apprentice relationship with a then-unknown Phil Spector. Although he was working with Leiber and Stoller at the time, it is unknown whether Spector assisted with the production of this record; however, many Spector fans have noticed similarities between this record and other music he would eventually produce on his own. Damita Jo had a hit with one of the answer songs of this era called “I’ll Save The Last Dance For You”. On September 9, 1965, the group performed the song live at the Cinnamon Cinder with Charlie Thomas lip-syncing the lyrics of Ben E. King vocals, along with fellow Drifters Johnny Moore and Eugene Pearson on backing vocals.

is the title of a popular song written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, first recorded in 1960 by The Drifters, with Ben E. King on lead vocals. In a 1990 interview, songwriter Doc Pomus tells the story of the song being recorded by the Drifters and originally designated as the B-side of the record. He credits Dick Clark with turning the record over and realizing “Save The Last Dance” was the stronger song. The Drifters’ version of the song, released a few months after Ben E. King left the group, would go on to spend three non-consecutive weeks at #1 on the U.S. pop chart, in addition to logging one week atop the U.S. R&B chart. In the UK The Drifters’ recording reached #2 in December 1960. This single was produced by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, two noted American music producers who at the time had an apprentice relationship with a then-unknown Phil Spector. Although he was working with Leiber and Stoller at the time, it is unknown whether Spector assisted with the production of this record; however, many Spector fans have noticed similarities between this record and other music he would eventually produce on his own. Damita Jo had a hit with one of the answer songs of this era called “I’ll Save The Last Dance For You”. On September 9, 1965, the group performed the song live at the Cinnamon Cinder with Charlie Thomas lip-syncing the lyrics of Ben E. King vocals, along with fellow Drifters Johnny Moore and Eugene Pearson on backing vocals.

In the song, the narrator tells his lover she is free to mingle and socialize throughout the evening, but to make sure to save him the dance at the end of the night. During an interview on Elvis Costello’s show Spectacle, Lou Reed, who worked with Pomus, said the song was written on the day of Pomus’ wedding while the wheelchair-bound groom watched his bride dancing with their guests. Pomus had polio and at times used crutches to get around. His wife, Willi Burke, however, was a Broadway actress and dancer. The song gives his perspective of telling his wife to have fun dancing, but reminds her who will be taking her home and “in whose arms you’re gonna be.”

Musicians on the Drifters’ recording were: Bucky Pizzarelli, Allen Hanlon (guitar), Lloyd Trotman (bass) and Gary Chester (drums).

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ub4yxVA4zDs[/embedyt]

Will You Love Me Tomorrow: The Shirelles

Is a song written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King. It was originally recorded in 1960 by the Shirelles, who took their single to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song is also notable for being the first song by a black all-girl group to reach number one in the United States. It has since been recorded by many artists over the years, including a 1971 version by co-writer Carole King.

Is a song written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King. It was originally recorded in 1960 by the Shirelles, who took their single to number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song is also notable for being the first song by a black all-girl group to reach number one in the United States. It has since been recorded by many artists over the years, including a 1971 version by co-writer Carole King.

Background

In 1960, the American girl group the Shirelles released the first version of the song as Scepter single 1211, with “Boys” on the B-side. The single’s first pressing was labelled simply “Tomorrow”, then lengthened later. When first presented with the song, lead singer Shirley Owens (later known as Shirley Alston-Reeves) did not want to record it, because she thought it was “too country.” She relented after a string arrangement was added. However, Owens recalled on Jim Parsons’ syndicated oldies radio program, Shake Rattle Showtime, that some radio stations had banned the record because they had felt the lyrics were too sexually charged. The song is in AABA form.

Reception

This version of the song, with session musicians Paul Griffin on piano and Gary Chester on drums, as of 2009 was ranked as the 162nd greatest song of all time, as well as the best song of 1960, by Acclaimed Music. It was ranked at #126 among Rolling Stone ‘s list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. Billboard named the song #3 on their list of 100 Greatest Girl Group Songs of All Time.

The song later appeared on the soundtrack of Michael Apted’s Stardust.

Answer songs

Bertell Dache, a black demo singer for the Brill Building songwriters, recorded an answer song entitled “Not just Tomorrow, But Always”. It has been erroneously claimed by some historians that Dache was a pseudonym for Epic recording artist Tony Orlando, whose recording of the original song had not been released as Don Kirshner thought the lyric was convincing only as sung by a woman. However, an ad for United Artists Records which appeared in Billboard during 1961 featured a photo of the singer which conclusively proved that Dache was not Tony Orlando.

The Satintones, an early Motown group, also recorded an answer song called “Tomorrow and Always,” which used the same melody as the original but initially neglected to credit King and Goffin. Following a threat of litigation, later pressings of the record included proper credit. The Satintones’ versions are included in the box set The Complete Motown Singles, Volume 1: 1959–1961.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbxxkwBQk_o[/embedyt]

Blue Moon: The Marcels

is a classic popular song written by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart in 1934, and has become a standard ballad. It may be the first instance of the familiar “50s progression” in a popular song.

is a classic popular song written by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart in 1934, and has become a standard ballad. It may be the first instance of the familiar “50s progression” in a popular song.

The song was a hit twice in 1949 with successful recordings in the US by Billy Eckstine and Mel Tormé. In 1961, “Blue Moon” became an international number one hit for the doo-wop group The Marcels, on the Billboard 100 chart and in the UK Singles chart. Over the years, “Blue Moon” has been covered by various artists including versions by Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday, Elvis Presley, The Mavericks, Dean Martin, The Supremes and Rod Stewart.

Bing Crosby included the song in a medley on his album On the Happy Side (1962). It is also the anthem of English Premier League football club Manchester City, who have adapted the song slightly.

Marcels version

Background

The Marcels, a doo-wop group, also recorded the track for their album Blue Moon. In 1961, the Marcels had three songs left to record and needed one more. Producer Stu Phillips did not like any of the other songs except one that had the same chord changes as “Heart and Soul” and “Blue Moon”. He asked them if they knew either, and one knew “Blue Moon” and taught it to the others, though with the bridge or release (middle section – “I heard somebody whisper…”) wrong. The famous introduction to the song (“bomp-baba-bomp” and “dip-da-dip”) was an excerpt of an original song that the group had in its act.

Reception

The record reached number one on the Billboard Pop chart for three weeks and number one on the R&B chart. It also peaked at #1 on the UK Singles Chart. The Marcels’ version of “Blue Moon” sold a million copies, and was awarded a gold disc.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qoi3TH59ZEs[/embedyt]

Runaway: Del Shannon

is a number-one Billboard Hot 100 song made famous by Del Shannon in 1961. It was written by Shannon and keyboardist Max Crook, and became a major international hit. It is No. 472 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, compiled in 2010.

is a number-one Billboard Hot 100 song made famous by Del Shannon in 1961. It was written by Shannon and keyboardist Max Crook, and became a major international hit. It is No. 472 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time, compiled in 2010.

Singer-guitarist Charles Westover and keyboard player Max Crook performed together as members of “Charlie Johnson and the Big Little Show Band” in Battle Creek, Michigan, before their group won a recording contract in 1960. Westover took the new stage name “Del Shannon”, and Crook, who had invented his own clavioline-based electric keyboard called a Musitron, became “Maximilian”.

After their first recording session for Big Top Records in New York City had ended in failure, their manager Ollie McLaughlin persuaded them to rewrite and re-record an earlier song they had written, “Little Runaway”, to highlight Crook’s unique instrumental sound. On January 21, 1961, they recorded “Runaway” at the Bell Sound recording studios, with Harry Balk as producer, Fred Weinberg as audio engineer and also session musician on several sections: session musician Al Caiola on guitar, Moe Wechsler on piano, and Crook playing the central Musitron break. Other musicians on the record included Al Casamenti and Bucky Pizzarelli on guitar, Milt Hinton on bass, and Joe Marshall on drums. Bill Ramall, who was the arranger for the session, also played baritone sax. After recording in A minor, producer Balk sped up the recording to pitch just below a B-flat minor. “Runaway” was released in February 1961 and was immediately successful. On April 10 of that year, Shannon appeared on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand helping to catapult it to the number one spot on the Billboard charts where it remained for four weeks. Two months later, it also reached number one in the UK. On the R&B charts, “Runaway” peaked at number three. The song was #5 on the Billboard Hot 100 Year-End Chart in 1961.

Del Shannon re-recorded it in 1967 as “Runaway ’67”. This version was issued as a single but failed to make the Hot 100.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NMufLXrFIg8[/embedyt]

Runaround Sue: Dion

is a pop song, in a doo-wop style, originally a US No. 1 hit for the singer Dion during 1961 after he split with the Belmonts. The song ranked No. 351 on the Rolling Stone list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. The song was written by Dion with Ernie Maresca, and tells the story of a disloyal lover.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y4NUZJMCJ20[/embedyt]

The Lion Sleeps Tonight: The Tokens

Is a song written and recorded originally by Solomon Linda with the Evening Birds for the South African Gallo Record Company in 1939, under the title “Mbube“. Composed in Zulu, it was adapted and covered internationally by many 1950s and ’60s pop and folk revival artists, including the Weavers, Jimmy Dorsey, Yma Sumac, Miriam Makeba and the Kingston Trio. In 1961, it became a number one hit in the United States as adapted in English with the best-known version by the doo-wop group the Tokens. It went on to earn at least US$15 million in royalties from cover versions and film licensing. The pop group Tight Fit had a number one hit in the UK with the song in 1982.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OQlByoPdG6c[/embedyt]

Breaking Up Is Hard to Do: Neil Sedaka

Is a song recorded by Neil Sedaka, and co-written by Sedaka and Howard Greenfield. Sedaka recorded this song twice, in 1962 and 1975, in two vastly different arrangements, and it is considered to be his signature song. Another song by the same name had previously been recorded by Jivin’ Gene [Bourgeois] and The Jokers, in 1959.

escribed by AllMusic as “two minutes and sixteen seconds of pure pop magic,” “Breaking Up Is Hard to Do” hit number one on the Billboard Hot 100 on August 11, 1962 and peaked at number twelve on the Hot R&B Sides chart. The single was a solid hit all over the world, reaching number 7 in the UK, sometimes with the text translated into foreign languages. For example, the Italian version was called “Tu non lo sai” (“You Don’t Know”) and was recorded by Sedaka himself.

On this version, background vocals on the song are performed by the female group The Cookies.

The personnel on the original recording session included: Al Casamenti, Art Ryerson, and Charles Macy on guitar; Ernie Hayes on piano; George Duvivier on bass; Gary Chester on drums; Artie Kaplan on saxophone; George Devens and Phil Kraus on percussion; Seymour Barab and Morris Stonzek on cellos; and David Gulliet, Joseph H. Haber, Harry Kohon, David Sackson, and Louis Stone on violins.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tbad22CKlB4[/embedyt]

Surf City: Jan and Dean

is a song written by Brian Wilson and Jan Berry about a fictitious surf spot where there are “two girls for every boy.”[1] It was first recorded and made popular by the American duo Jan and Dean in 1963, and their single became the first surf song to become a national number-one hit.

is a song written by Brian Wilson and Jan Berry about a fictitious surf spot where there are “two girls for every boy.”[1] It was first recorded and made popular by the American duo Jan and Dean in 1963, and their single became the first surf song to become a national number-one hit.

Jan and Dean version

The first draft of the song, with the working title “Goody Connie Won’t You Come Back Home”, was written by Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys. While at a party with Jan Berry and Dean Torrence, Wilson played them “Surfin’ U.S.A.” on the piano. Berry and Torrence suggested that they do the song as a single, but Wilson refused, as “Surfin’ U.S.A.” was intended for the Beach Boys. Wilson then suggested that the duo record “Surf City” instead, demoing the opening, verse, and chorus. Wilson had lost interest in the song and believed he was never going to complete it himself. Berry later contributed additional writing to the song, while Torrence also contributed several phrases, but never insisted that he be given writing credit.

Hal Blaine, Glen Campbell, Earl Palmer, Bill Pitman, Ray Pohlman and Billy Strange are identified as players for the single per the American Federation of Musicians contract.

Released in May 1963, two months later it became the first surf song to reach number one on national record charts, remaining at the top of Billboard Hot 100 for two weeks. The single crossed over to the Billboard R&B Chart where it peaked at number 3. It also charted in the UK, reaching number 26. Before the single, Jan and Dean made music which was largely inspired by East Coast black vocal group records. The success of “Surf City” gave them a unique sound and identity which would be followed by five more top ten hits inspired by Los Angeles surf or hot rod life.

The Beach Boys’ manager and Wilson’s father Murry was reportedly irate about the song, believing that Brian had wasted a number one record which could have gone to his group, the Beach Boys. Brian later told Teen Beat, “I was proud of the fact that another group had had a number 1 track with a song I had written … But dad would hear none of it. … He called Jan a ‘record pirate

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6dJO8nAoYY[/embedyt]

My Boyfriend’s Back: The Angels

as a hit song in 1963 for the Angels, an American girl group. It was written by the songwriting team of Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein and Richard Gottehrer (a.k.a. FGG Productions who later formed the group the Strangeloves). The recording, employing the services of drummer Gary Chester, was originally intended as a demo for the Shirelles, but ended up being released as recorded. The single spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, and reached number two on the R&B Billboard.

as a hit song in 1963 for the Angels, an American girl group. It was written by the songwriting team of Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein and Richard Gottehrer (a.k.a. FGG Productions who later formed the group the Strangeloves). The recording, employing the services of drummer Gary Chester, was originally intended as a demo for the Shirelles, but ended up being released as recorded. The single spent three weeks at number one on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, and reached number two on the R&B Billboard.

The song is a word of warning to a would-be suitor who, after the narrator of the song rebuffed his advances, went on to spread nasty rumors accusing the narrator of romantic indiscretions. Now, the narrator declares, her boyfriend is back in town and ready to settle the score, and she tells the rebuffed would-be suitor to watch his back.

Other musicians on the record included Herbie Lovelle on drums, Billy Butler, Bobby Comstock, and Al Gorgoni on guitar, and Bob Bushnell overdubbing on an electric and an upright bass. This song also features a brass section as well.

The song begins with a spoken recitation from the lead singer that goes: “He went away, and you hung around, and bothered me every night. And when I wouldn’t go out with you, you said things that weren’t very nice.”

The album version features the line: “Hey. I can see him comin’/ Now you better start a runnin'”. before the instrumental repeat of the bridge section and a repeat of one stanza from the refrain, before the coda section.

The inspiration for the song was when co-writer Bob Feldman overheard a conversation between a high school girl and the boy she was rebuffing.[4]

Billboard named the song #24 on their list of 100 Greatest Girl Group Songs of All Time

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5NuofNHKbVc[/embedyt]